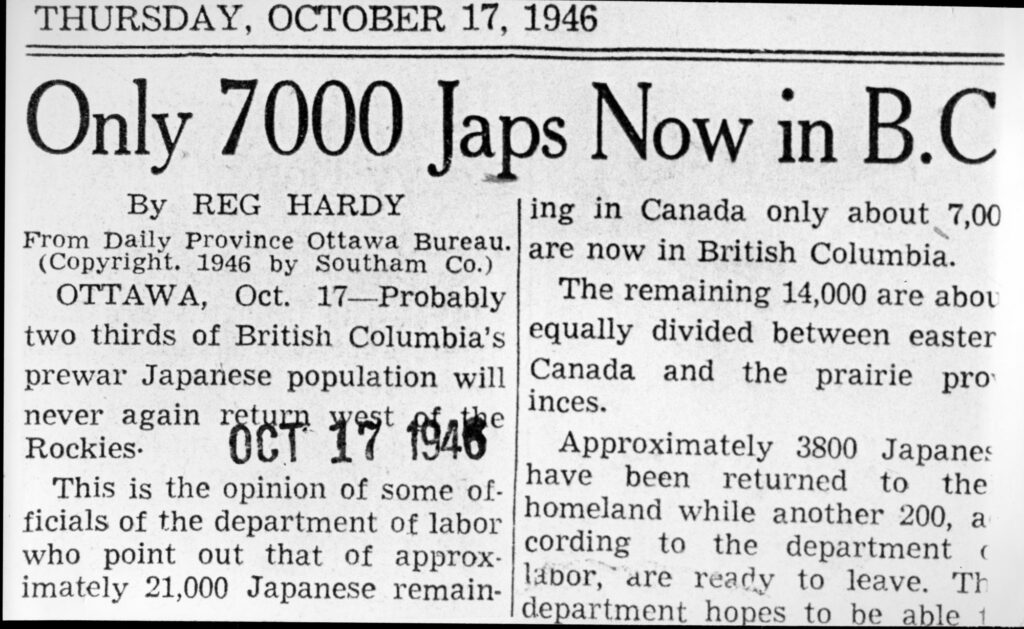

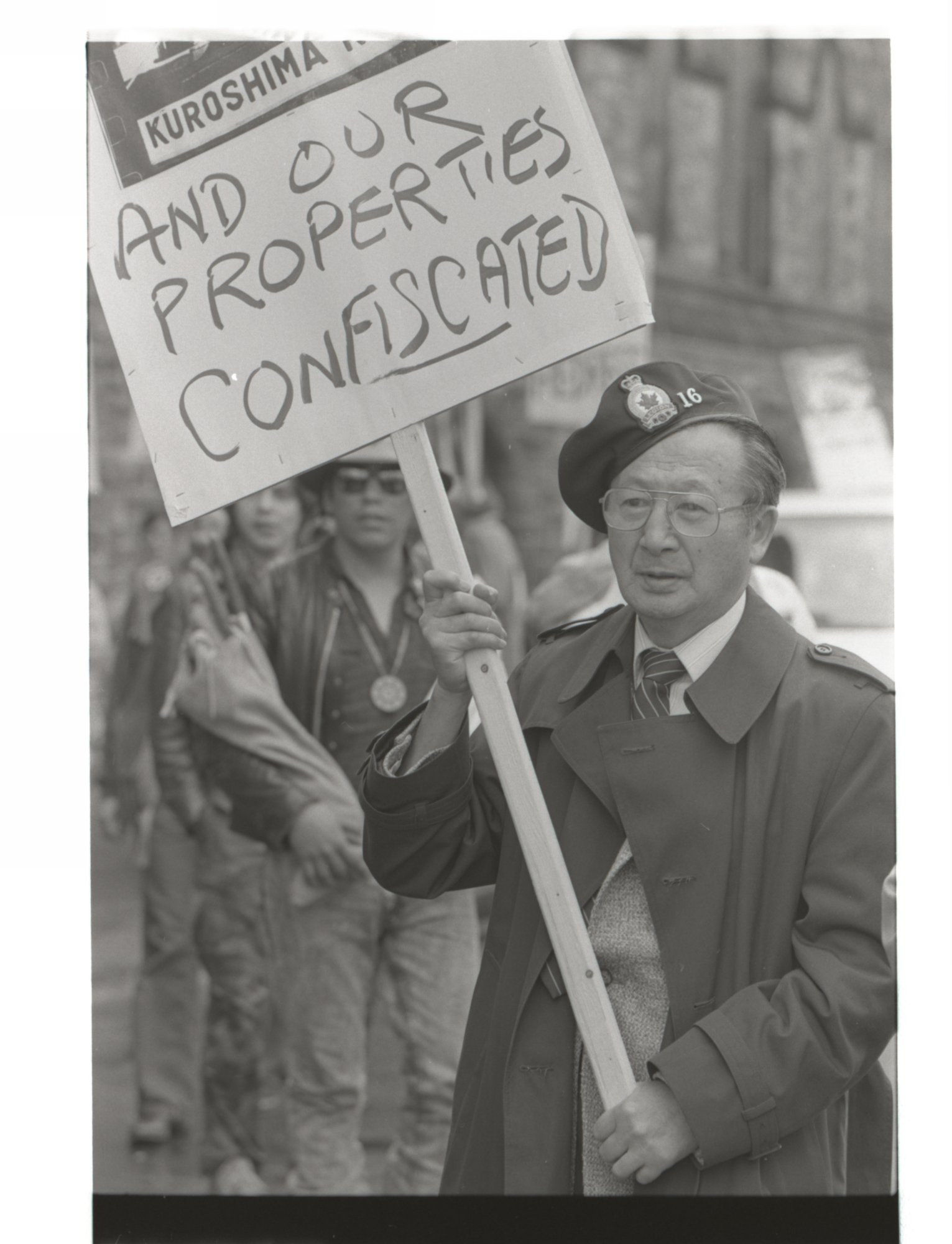

Unlike interned Japanese Americans, the Canadian internees were not permitted to return to their homes (most of which were in BC) at the end of the war. Instead, Japanese Canadians were given two difficult choices: disperse east of the Rocky Mountains or be “repatriated” to Japan (Ito, 1984).

East of the Rockies

After the war, most former internees settled in parts of Canada east of the Rockies. This was not a straightforward matter for them. They were unwelcome in many locations after the war.

“Evacuation stigmatized the entire Japanese population and gave the spurious colour of official approval to racism, yet the federal government…failed to mount an organized public information programme that might have made relocation easier for the evacuees and acceptable to the host communities…Still, since the evacuation was, in effect, a certification by the federal government that all Japanese were dangerous, the protests against receiving the evacuees by other areas in Canada were virtually unassailable (Adachi, p 280)”.

In some of the larger cities in eastern Canada such as Winnipeg and Toronto, groups were organized to assist Japanese Canadians move from internment camps and sugar beet farms. Some were societies of Japanese Canadians who had previously settled in those locations; some were based out of local churches (such as the United Church and Salvation Army) and the YMCA.

“Repatriation” to Japan

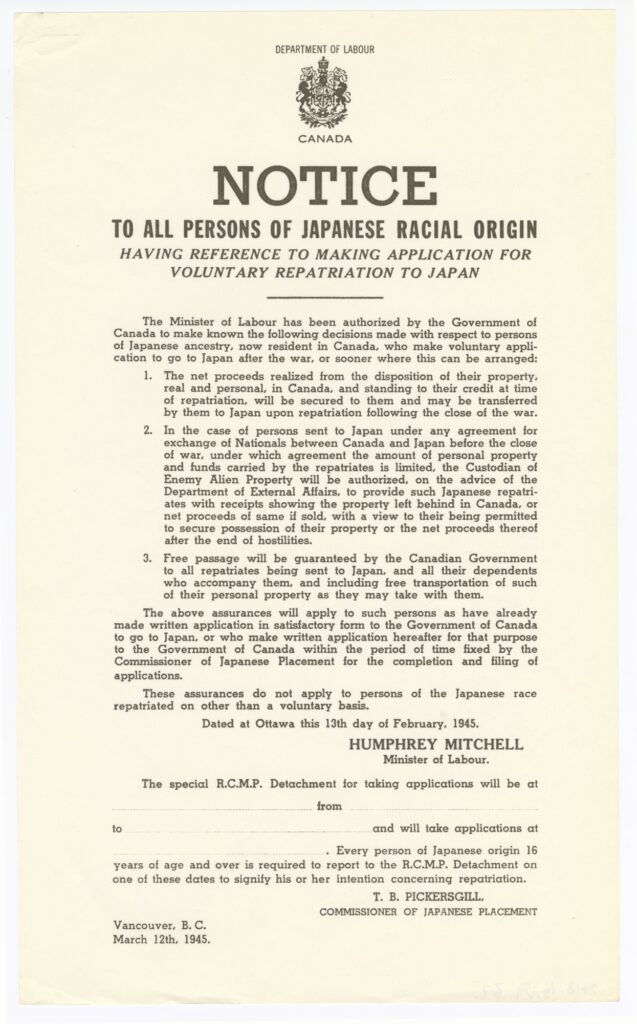

In August 1944, The Government announced its “reconstruction” program to disperse Japanese Canadians throughout the country, to separate those who were “loyal” from those who were “disloyal”, and to “repatriate” the disloyal to Japan (page 276). The “quasi-judicial commission” that was to ascertain who was loyal and who was not was never set up (Theurer, p. 211).

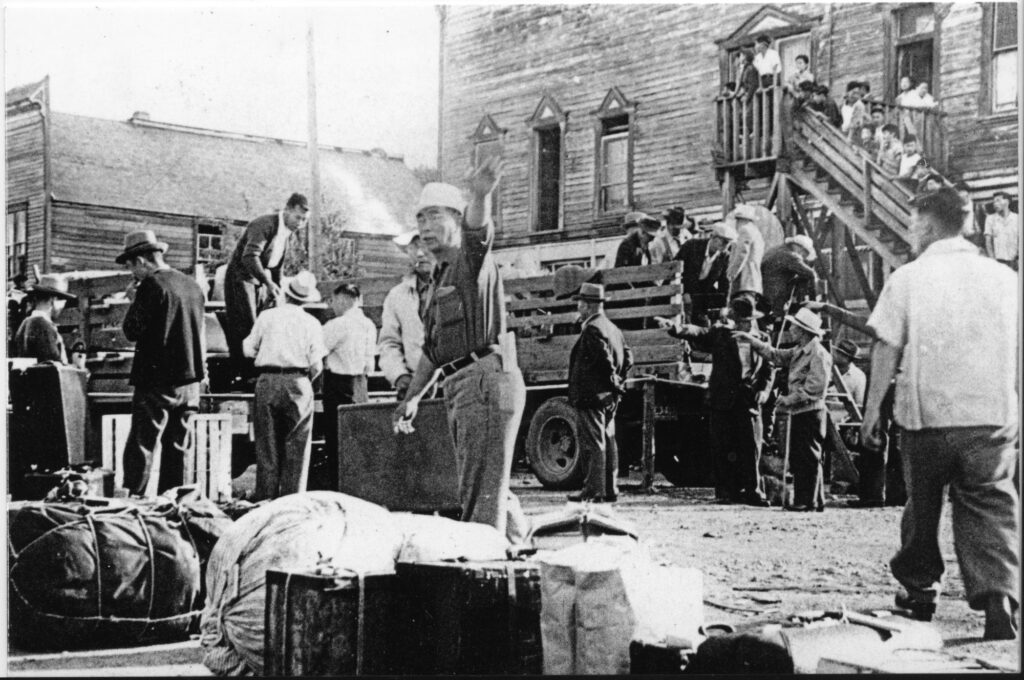

At the beginning of 1945, many internees had already left the camps. Anyone remaining was ordered to fill out a repatriation survey to determine their loyalty to Canada. They were offered either “repatriation” to Japan or the order to immediately move east of the Rocky Mountains. They were given a month to make their decision. This choice resulted in much confusion and disagreement among the Japanese Canadian community. Approximately 10,632 people (half the Japanese Canadian population) signed the “repatriation” forms (Adachi, p. 301), under pressure from the government, who wanted them to leave the country. Pressure also came from within the camps; most of the people that remained in the camps signed for “repatriation” to demonstrate their anger at Canada for their treatment (Suzuki, 1987, p. 76).

However, nearly half of those that signed up later applied to rescind their signatures to stay.

Opposition to the idea of sending Canadian citizens to Japan began at this point.

In the summer of 1945, many of those who had signed up for “repatriation” wanted to change their request to “stay”. As Japan surrendered, the numbers of those wanting to remain in Canada increased, saying that they had been intimidated into signing up for repatriation (Theurer, 208).

Starting on May 31, 1946, almost 4000 former internees (about 2000 of whom were aging issei and 1300 of whom were children under 16) were sent to Japan on “repatriation ships”. Many were Canadian citizens. They arrived in a wasteland ravaged by bombs, unemployment, and food shortages. Many nisei had never set foot in Japan before but felt obliged to stay with their parents to help them; they were displaced persons for a second time.