On October 7, 1967, nisei veterans, including S-20 students and staff, from the Second World War held a reunion in Toronto. The reunion coincided with the celebration of Canada’s centennial. Veterans were by then living in many parts of Canada, the US, and Asia. The organizing committee was able to locate 60% of the veterans. Many had not seen each other for 22 years. 55 veterans attended, including 41 nisei. The guest speaker was Judy LaMarsh, an S-20 graduate who in 1967 was Canada’s federal secretary of state.

Pictured from left to right:

Front row: George Suzuki, George Tanaka, Sid Sakanashi, Kumy Yoshida, Roger Obata, John Fortin, Stum Shimizu, Sadao Nikaido, Bob Elliot, George Kadota

Second row: John Tani, James Miyasaka, Lloyd Graham, Roy Ito, Mickey Nobuto, Ed Bakony (Ottawa), Louis Suzuki, Ken Mozaki, Tom Sagara, Kiyo Ise, George Obokata, Frank Moritsugu, Kaide Shimizuki

Third row: Tad Ode, Jack Struthers, Lloyd Tomlinson, Harold Hirose, Mrs. Griffith, Llewellyn Fletcher (B.C.), Mrs. A..P. McKenzie, Tom Yamashita, Fernand Leduc (Que.), Mas Hyodo, Jin Ide, Shei Omura, Tad Goto, Jack Oki

Back row: Shig Oue, John McTavish (B.C.), Tak Kunitomo, Costello Sato, Bill Sasaki, Frank Matsubuchi, Kats Oikawa, Denise Sommerville, Bill Sommerville, Honorable Judy LaMarsh, Peter McKenzie, Frank Haleyy (Alberta), Bill Hunter, Min Yatabe, Roy Matsui, Cecil Brett, Eiji Yatabe, Ray Takeuchi, Frank Takayesu, Dick Adachi, Yosh Hyodo, Dave Bee

The reunion was reported in the Globe and Mail newspaper and by CBC television. The S-20 and Nisei Veterans Association was established as a result of the 1967 reunion.

This association kept veterans in touch with each other, maintained a newsletter, organized meetings, scholarships, and travel for members, including a trip to Japan in 1970 to attend Expo 70 in Osaka. The association provided support for veteran Roy Ito’s books, We Went to War, and Stories of My People.

Japanese Canadians observed the centennial of the recognized arrival of the first issei in Canada, Manzo Nagano, in 1977. The centennial was commemorated with activities and celebrations across Canada, renewing confidence, cultural pride, and interest in heritage among Japanese Canadians. Japanese Canadians began to consider the issue of redress for their internment and wartime injustices, experiences that the nisei and issei had been previously reluctant to discuss with their family members (Yamada, 2000).

Nisei veterans were key organizers of the 1977 Centennial celebrations. Roger Obata was the chairman of the National Japanese Canadian Centennial Society. Shig Oue, public relations chair, arranged the donation to the province of Ontario of a 1200 lb solid bronze temple bell. The bell, now located at Ontario Place in Toronto, is a permanent reminder of the Japanese Canadian Centennial. George Obokata represented the Centennial Society in London, Ontario (Japanese Centennial Society, 1977).

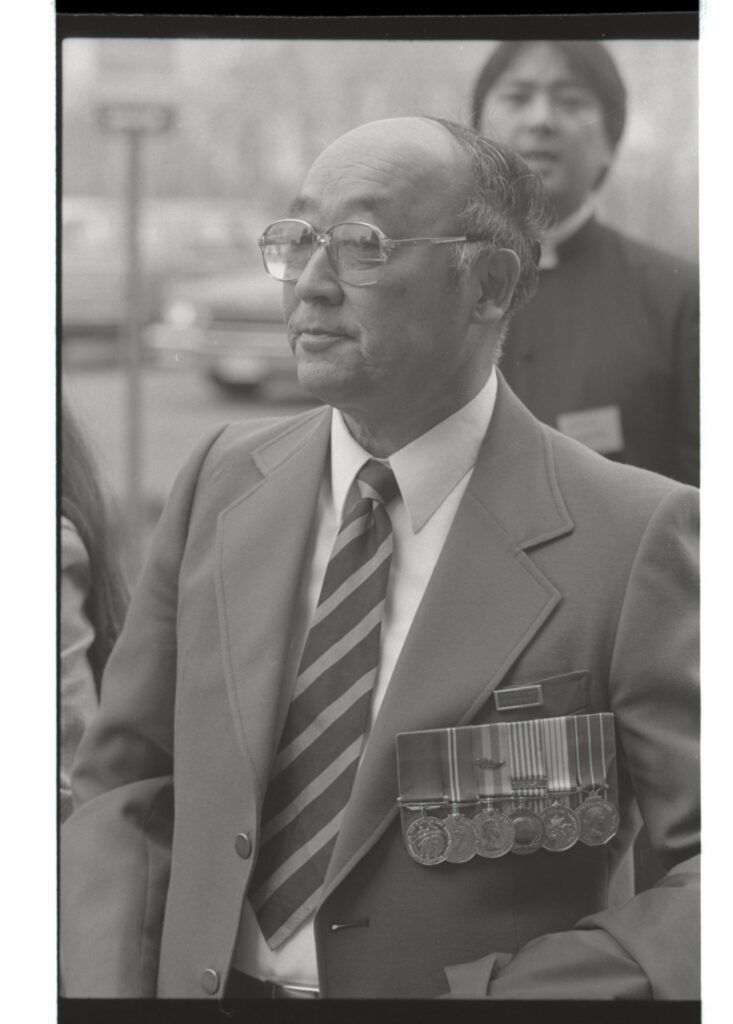

Nisei veterans were also at the core of the redress movement that concluded in 1988.

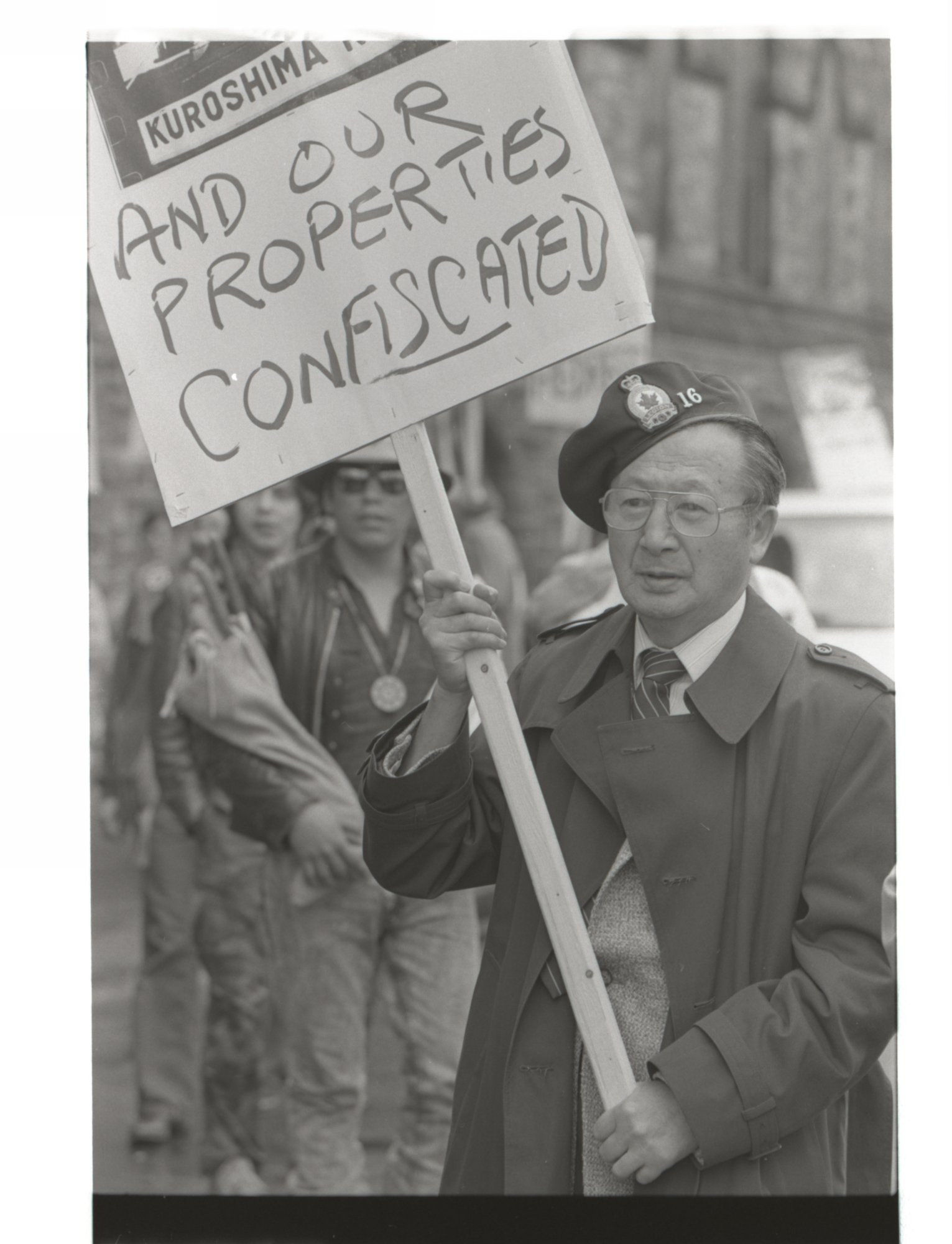

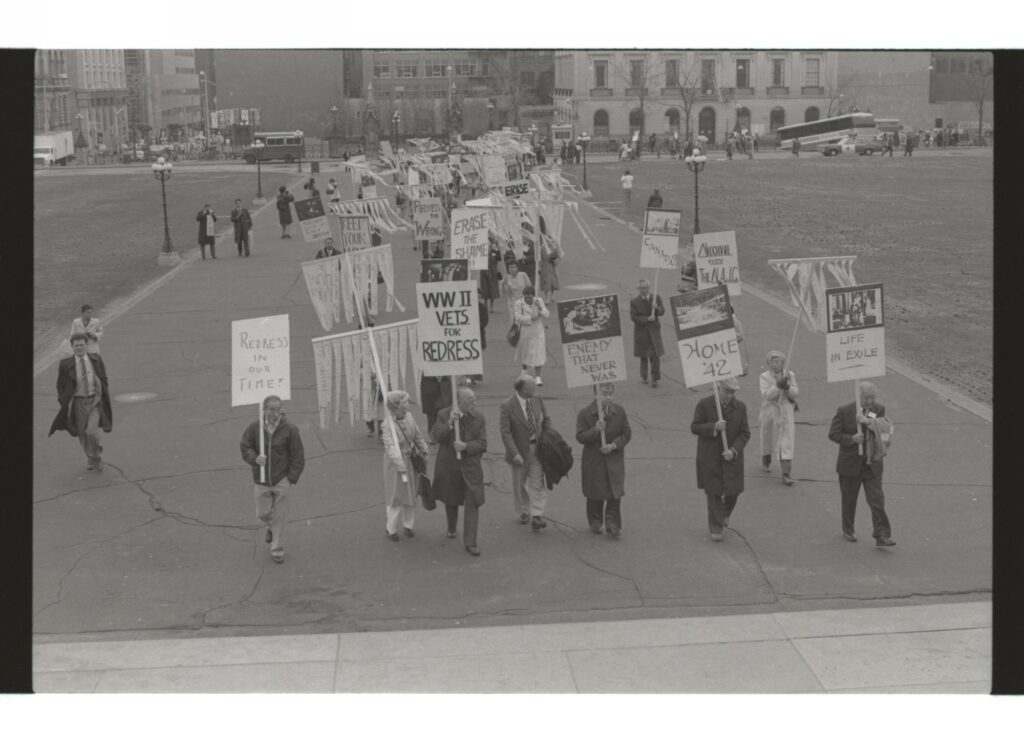

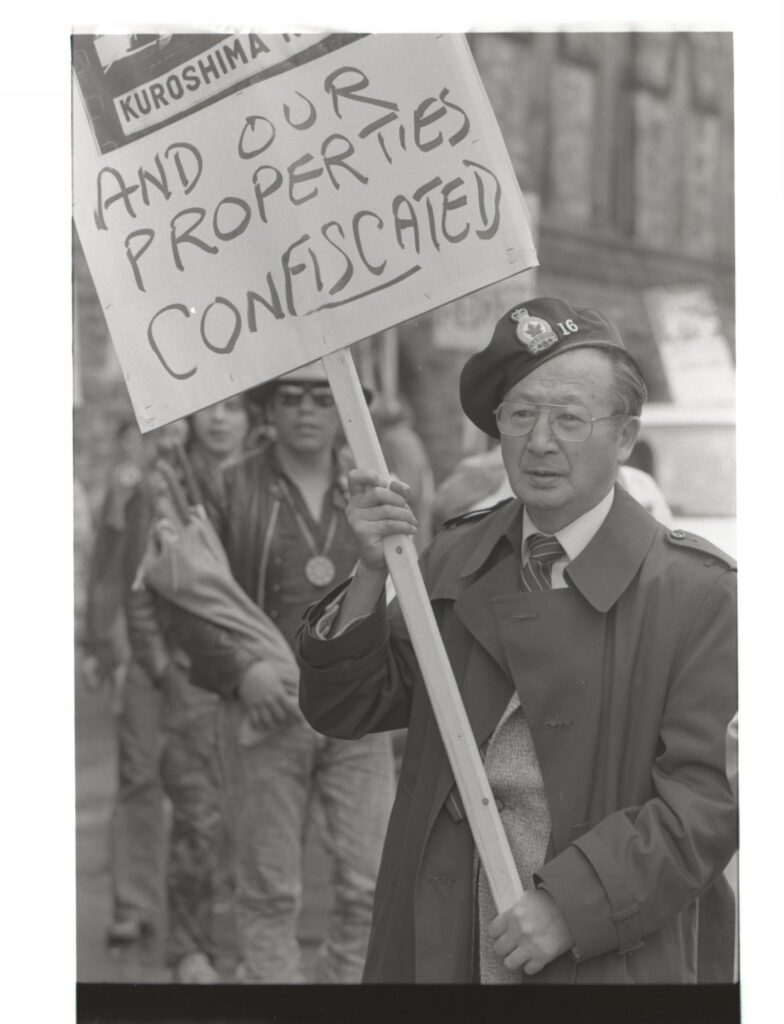

Art Miki, president of the NAJC (National Association of Japanese Canadian), led many hours of negotiation with the government to develop a compensation package for former internees and ensuring that information was disseminated to them. Among many other veterans, Roger Obata, Harold Hirose, and Dick Nakamura supported this work from different locations across the country. On April 14, 1998, the NAJC organized a redress rally on Parliament Hill in Ottawa. Veterans including Roger Obata, Roy Ito, Mas Kawanami, Fred Kagawa, Harold Hirose, and Jack Nakamoto marched in the rally.

On September 22,1988, Canada’s Conservative government under Prime Minister Brian Mulroney signed a redress agreement with the NAJC, acknowledging that Japanese Canadians had been unfairly treated in the 1940s. All surviving Japanese Canadians who had been affected by dispersal and dispossession were compensated, and a fund was disbursed to the NAJC to fund projects to benefit the community.

Japanese Canadian veterans made many contributions to their country years after their military service. Roger Obata became a member of the Order of Canada for his work on human rights during and after the Second World War, including redress. Tom Shoyama worked as an advisor to Tommy Douglas, helped to develop Medicare in the province of Saskatchewan and became Deputy Minister of Finance in the Canadian government; he became an Officer of the Order of Canada. Roy Ito became a school principal in Hamilton and authored two books. Jack Oki’s company did pioneering work in circuit board development (Theurer and Oue, 2021). Frank Moritsugu became a prominent journalist and author. James Oshiro, who participated in the European war, worked as a doctor in Alberta and eventually became the chancellor of the University of Lethbridge (Luckhurst, 1973). Second World War veterans Mitsukoshi Arikado, Masao Kawanami, and Joseph Takashima also served in the Korean War.

In 2011, after many years of lobbying by Mary and Tosh Kitagawa, the University of B.C. awarded honorary degrees to 76 Japanese Canadian students who had been expelled or unable to attend their graduation ceremonies after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Most of the students had been forced into internment camps (Ubyssey, 2012).

Among the 76 honored were three Second World War veterans: Tom Nishio, William Hiroshi Takeda, and Minoru Yatabe. Also among the 76 students were 14 former members of the Canadian Officers Training Corps at UBC: Teruo Ted Harada, Jim Hasegawa, George Ritsaburo Ito, Charles Hiroshi Kadota, Jack Kawaguchi, Richard Matsui, Koei Matsui, Akira Namba, George Ohama, Matthew S. Okuno, Shigeyuki Juki Otsuka, Roy Shinobu, Mits Michiyoshi Sumiya, and Edward Yoshioka. The family of Shigeyuki Otsuki commented in the commemorative yearbook published for this event that although Mr. Otsuki had been a member of the ROTC, “this was of no consequence in protecting him from the fury of the war” (Ubyssey, 2012).

Regarding the service of the nisei in the Second World War, Barry Broadfoot said: “So they went, and performed the job expected of them, often working in combat zones, and did the job well. They went overseas under a cloak of secrecy. No bands played for them, but of course, at that stage of the war, no bands played for anyone. When they returned, they came home in ones and twos and without fanfare.

And as a footnote, it was not until September, 1945, with the war over, that the Canadian government released the information that Japanese Canadians, those ‘enemy aliens’ of 1942, had played a small but vital role in the Allied victory in the Far East, in 1945.

Few people know this, even to this day. Many Japanese Canadians know it. The families of the veterans know it. The veterans know it. Somewhere among their possessions they have the medals to prove it (Broadfoot, 1979, p. 295)”.