The forced removal of Japanese Canadians had started on the day that Pearl Harbor was attacked, with the removal of 39 respected Japanese nationals from the community to Prisoner-of-War camps.

Eventually, 20,000 citizens would be uprooted and forcibly moved.

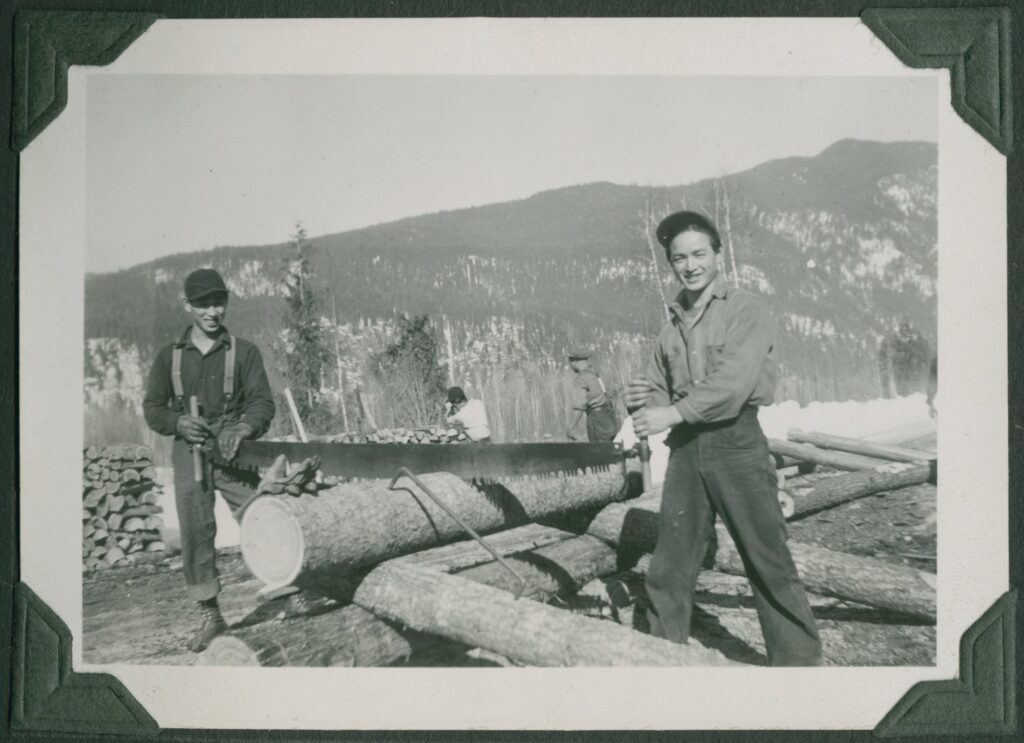

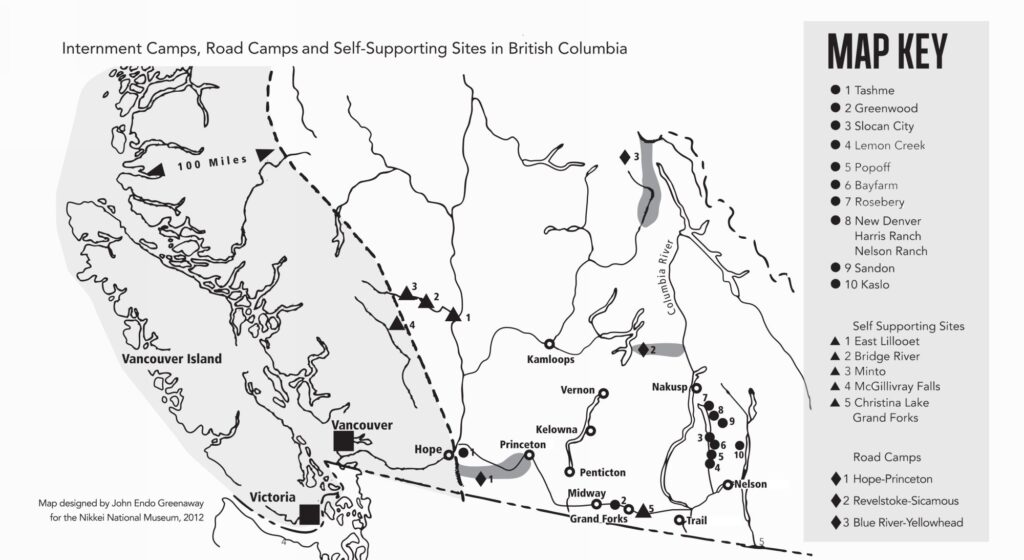

Facing pressure from British Columbia politicians, the Cabinet of Mackenzie King passed Order-in-Council P.C. 365 on January 16 which created a 100-mile Protected Zone extending from the BC coast. Male enemy aliens (Japanese nationals) aged 18-45 were removed from this zone beginning on February 24 and sent to work camps in the Rocky Mountains west of Jasper (Ito, 1984, p. 142, Theurer and Oue, 2021, p. 136).

On February 7, 1942, all male Japanese Canadian citizens between the ages of 18 and 45 were ordered to be removed from the Protected Zone.

On February 24, 1942, Order-in-Council P.C. 1486 was introduced, requiring all people of Japanese origin, regardless of citizenship, to be removed from the Protected Zone. Japanese nationals, naturalized Canadians, and Canadian-born citizens were all considered to be enemy aliens. Japanese women who were married to white men were allowed to stay in the Protected Zone. A curfew was established. Japanese Canadians were prevented by law from owning land or growing crops.

On March 4, 1942, the BC Security Commission was created to oversee the evacuation (Suzuki, 1987, p. 59).

In March 1942, Order-in-Council P.C. 1665 was introduced. Japanese Canadians were ordered to turn over property and belongings (plus items that ‘evacuees’ could not bring with them) to the Custodian of Enemy Alien Property as a “protective measure only.” Homes, farms and properties of Japanese Canadians were seized by the Custodian. Vehicles, cameras, radios, and firearms were confiscated.

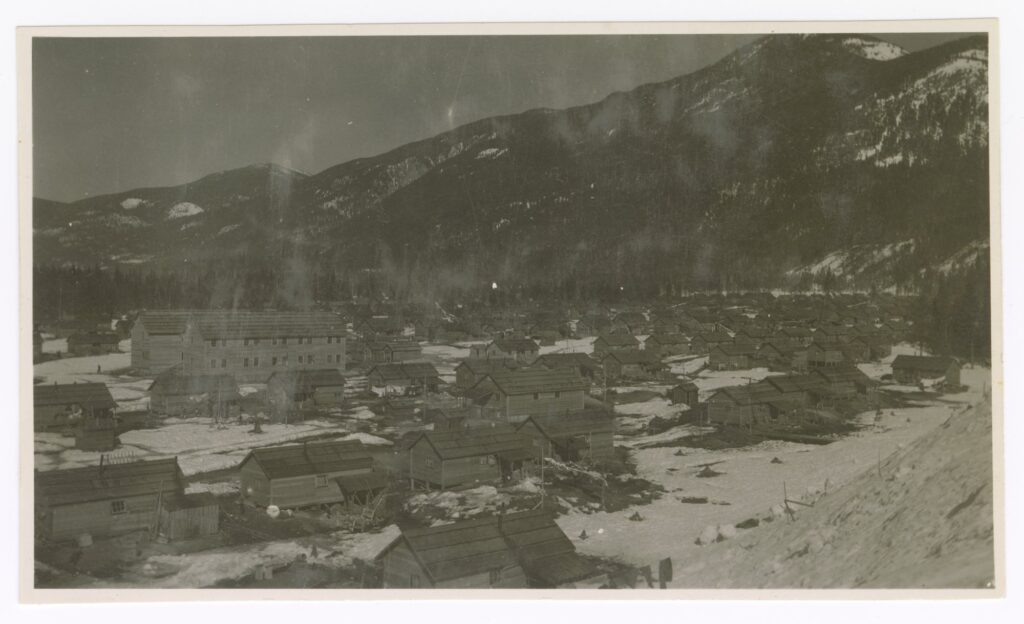

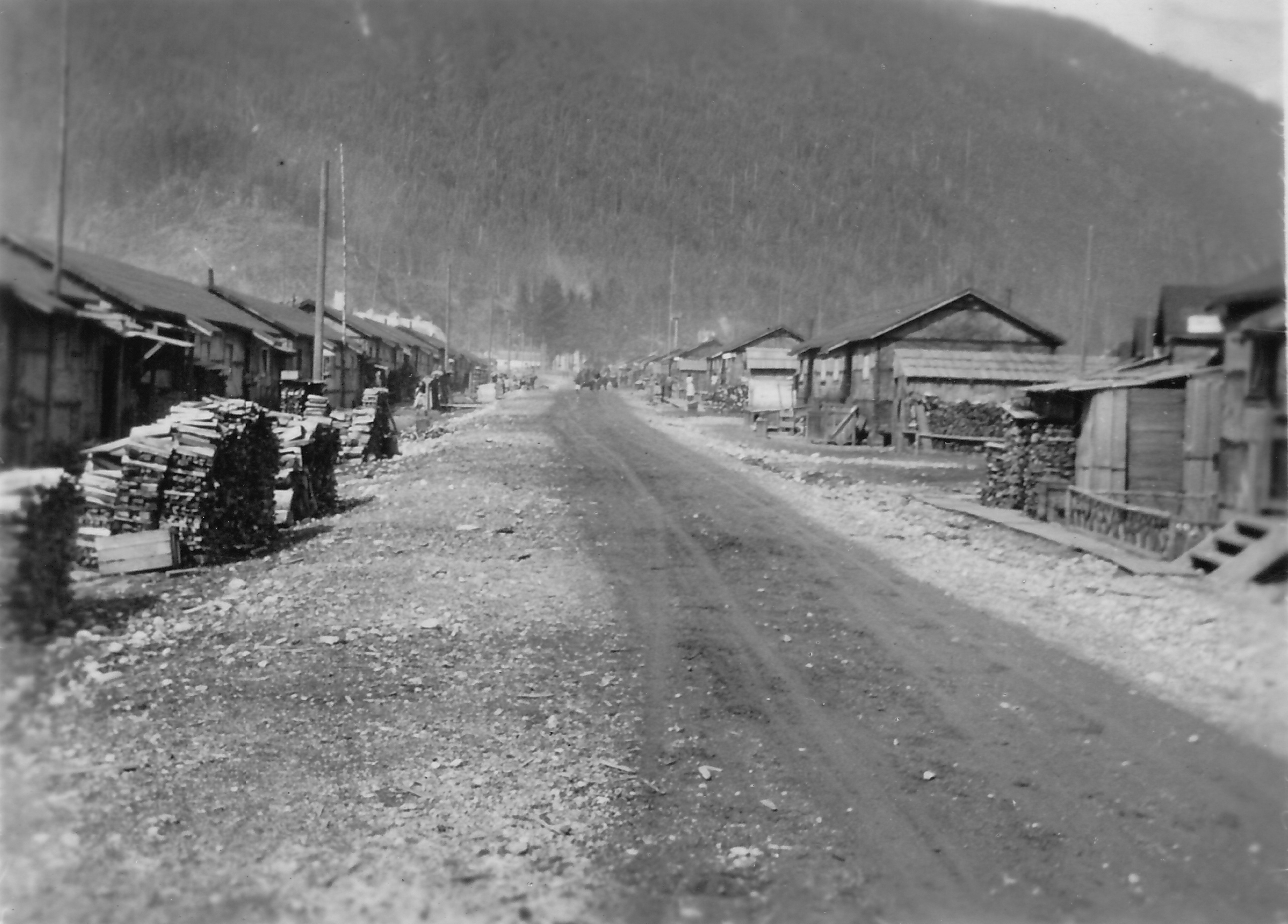

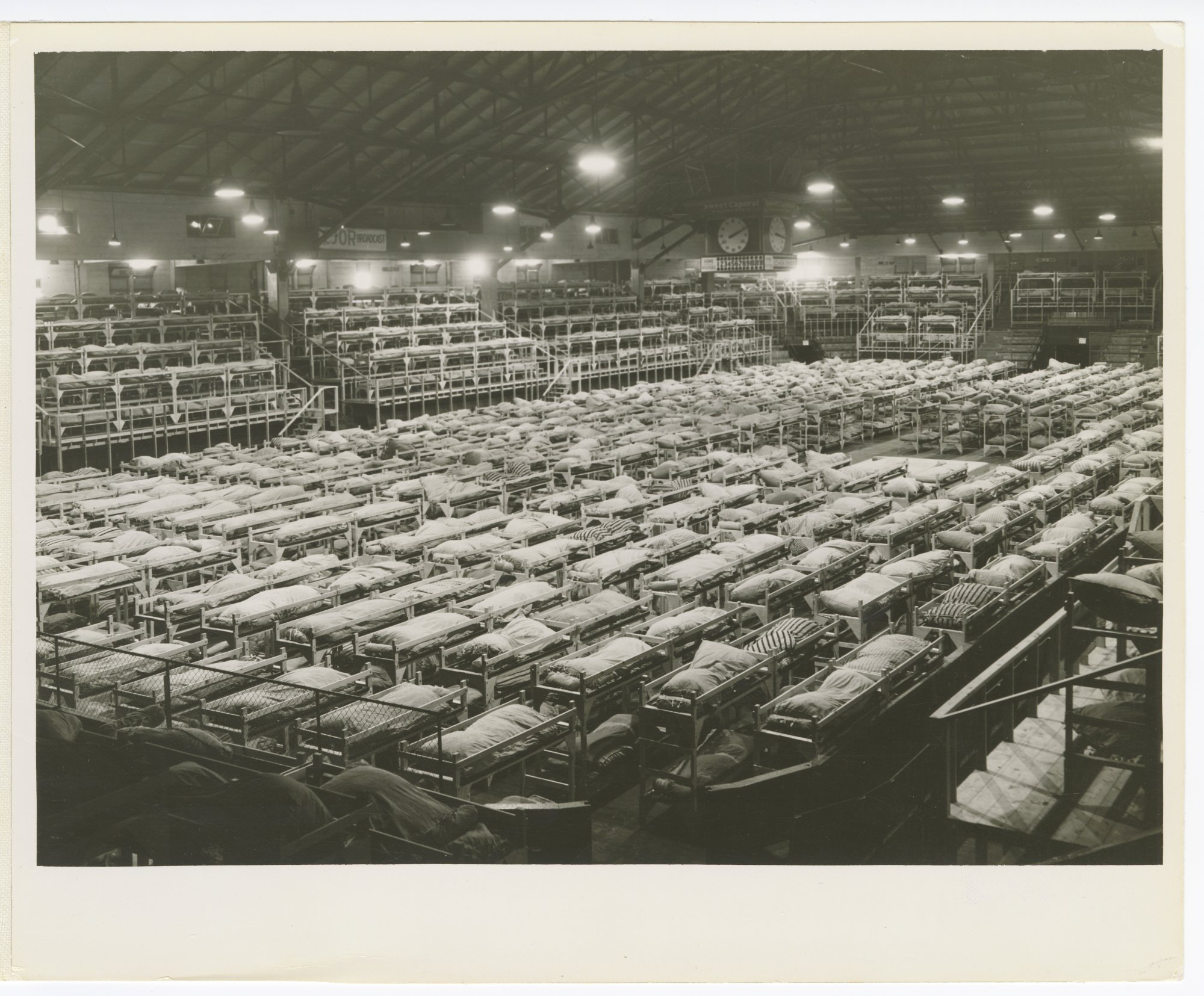

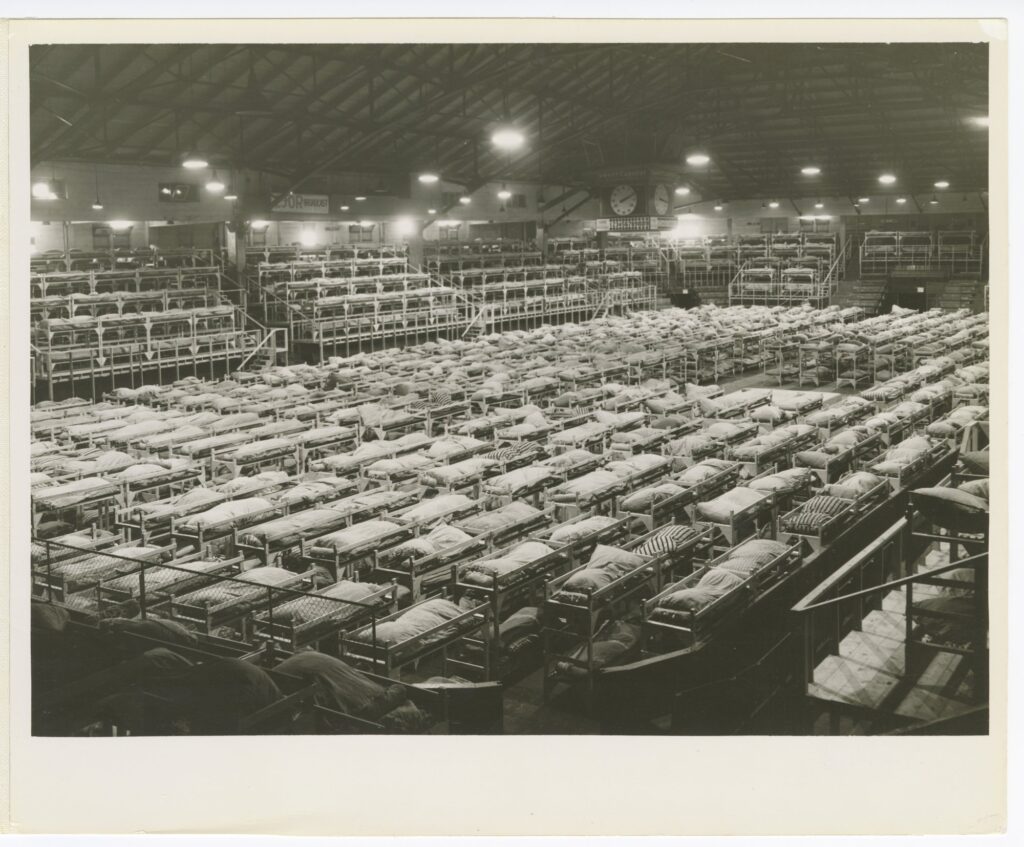

Temporary detention of Japanese Canadians at the livestock building of Vancouver’s Hastings Park began. Able-bodied men were sent to road construction camps around the country and women, children and elderly people were forced to go to internment camps, most of which were ghost towns in the BC interior, outside the Protected Area. Living conditions in the camp were very crowded and many families were unprepared for the cold winters in tents and poorly insulated buildings. All mail was censored. Families who wished to stay together were sent to sugar beet farms in Alberta, Manitoba, and Ontario to work and live under very harsh conditions. Some people were only given 24 hours to pack their belongings and leave. Adults were limited to 150 pounds of baggage, and children, 75 pounds. Those who protested about denial of their rights were sent to the Petawawa and Angler POW camps in Ontario, surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards.

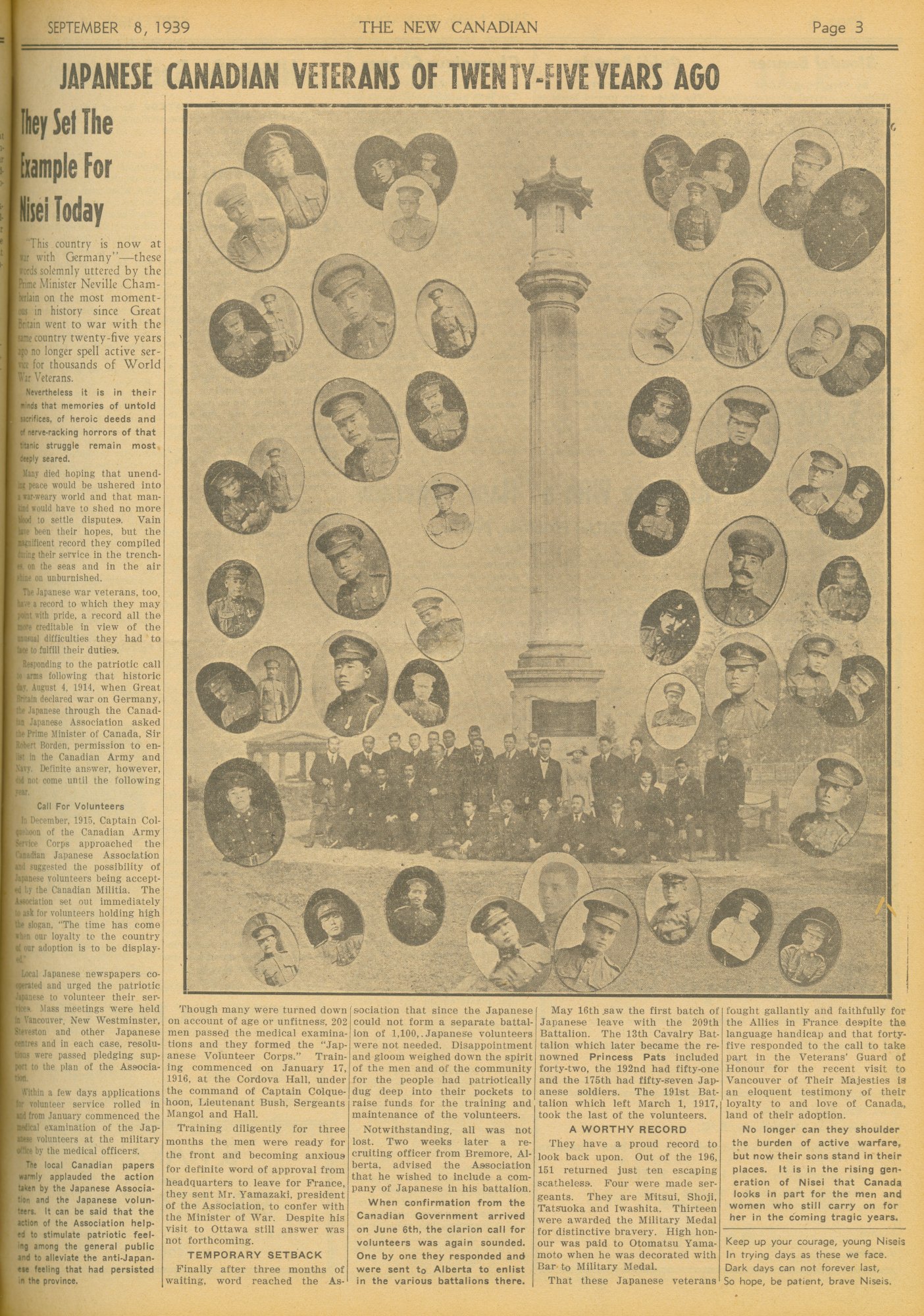

Issei veterans from the First World War learned that winning the franchise in 1931 and various medals for their bravery did not protect them from internment. Land, including farms, that the veterans had been granted from the Soldiers Settlement Board in 1919, was confiscated and sold during their internment. Only one First World War veteran, Zennosuke Inouye, regained his land after internment.

The provincial and federal governments argued about schooling for children in the internment camps. The federal government finally hired inexperienced nisei teachers for grades 1 to 8. The young children were taught by high school graduates who had taken a one-month intensive teaching course. High school students paid for correspondence courses or paid fees to attend schools. In some cases, they attended classes organized by Catholic, Anglican, and United churches.

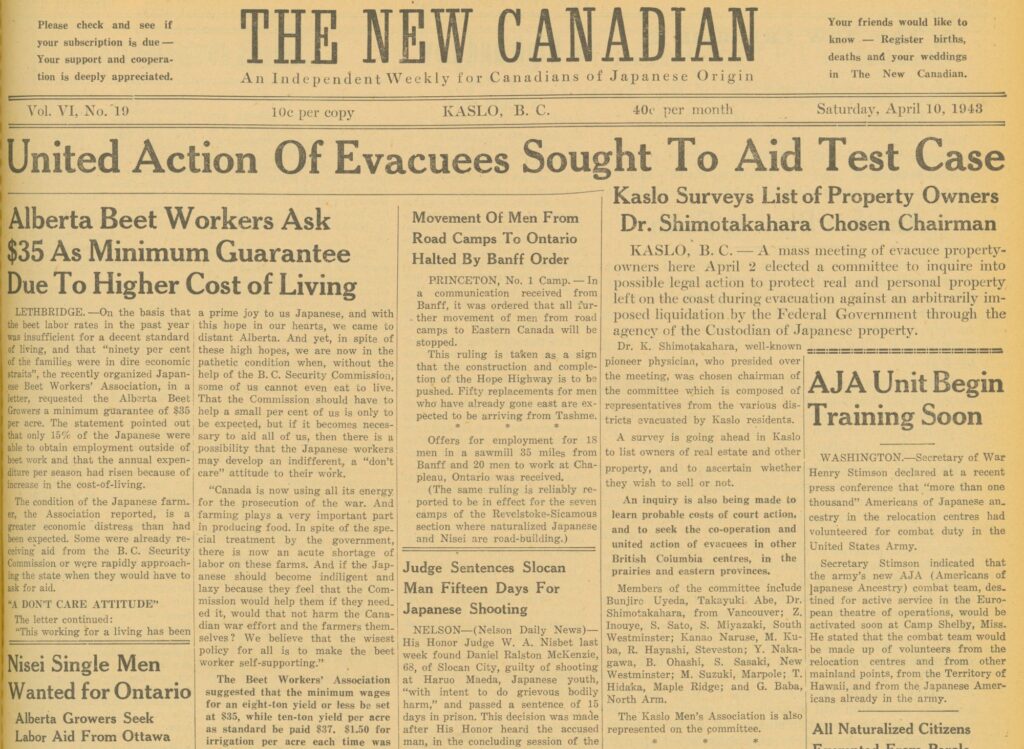

The New Canadian Newspaper remained open and was moved to Kaslo, one of the ghost towns. The New Canadian became a bilingual English/Japanese newspaper and was essential in maintaining communication between those who were scattered in many locations. It was also used by the Canadian government to publish public announcements to the scattered Japanese Canadian community.

Removing the Japanese from the workforce had a major impact on BC’s economy. The fishing boats and equipment seized from the Japanese were quickly sold, and the boats were soon operating with non-Japanese crews. In June 1942, the Director of Soldier Settlement was allowed to purchase or lease vacated farms. The Custodian of Enemy Alien Property sold the boats and farms belonging to the internees without their knowledge or consent (Theurer and Oue, 2021, p. 186). Internees received money from the sale, but most received far less than market value once various agents, lawyers and other middlemen were paid. Internees needed the money to pay for the costs of their own internment.

By the end of 1942, Japanese Canadians had been forcefully removed to the following locations:

12,029 prison camps in the BC interior

945 labour camps

3991 sugar beet farms in the prairies and Ontario

1161 self-supporting camps outside the Protected Zones

699 prisoner-of-war camps in Ontario

42 deported to Japan

111 incarcerated in Vancouver

105 hospitalized in Hastings Park, Vancouver

Approximately 2,000 Japanese Canadians were living outside the Protected Zone and allowed to remain in place, but subject to registration, restriction of activities, travel, and confiscation of prohibited items. 1359 were provided with special work permits that allowed them to work inside the Protected Zone (Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre, undated).

In 1943, the Custodian of Enemy Alien Property began to sell other belongings of internees without their consent.

British Columbians did not want the Japanese Canadians to return to BC and constantly lobbied to have the internees moved eastward or deported to Japan. In order to encourage settlement in eastern Canada, improvements to the camps were discontinued (Theurer and Oue, 2021, p. 189). People were allowed to leave the camps if they agreed to settle east of the Rocky Mountains. “BC.’s characterization of Japanese Canadians as dangerous subversives had been so effective that few people actually wanted them living in their communities, complicating the government’s efforts to settle evacuees in the east. For most of the Japanese, leaving the camps voluntarily was not an inviting prospect because they faced discrimination, uncertain employment prospects, and unjust living restrictions (Theurer and Oue, 2021, p. 190)”. They were afraid they would experience the same racial prejudice that they had encountered in BC.

The Japanese Canadian Committee for Democracy was organized in 1943 by BC nisei (mainly UBC students) including George Tanaka and Roger Obata, who had moved from BC to Toronto. It helped Japanese Canadians with resettlement and with problems such as the loss of their property and belongings. It also fought against the deportation of internees to Japan. The Cooperative Committee on Japanese Canadians, comprised of YWCA council members and church societies, was also established in 1943 to help internees from BC with resettlement (Anonymous, undated).