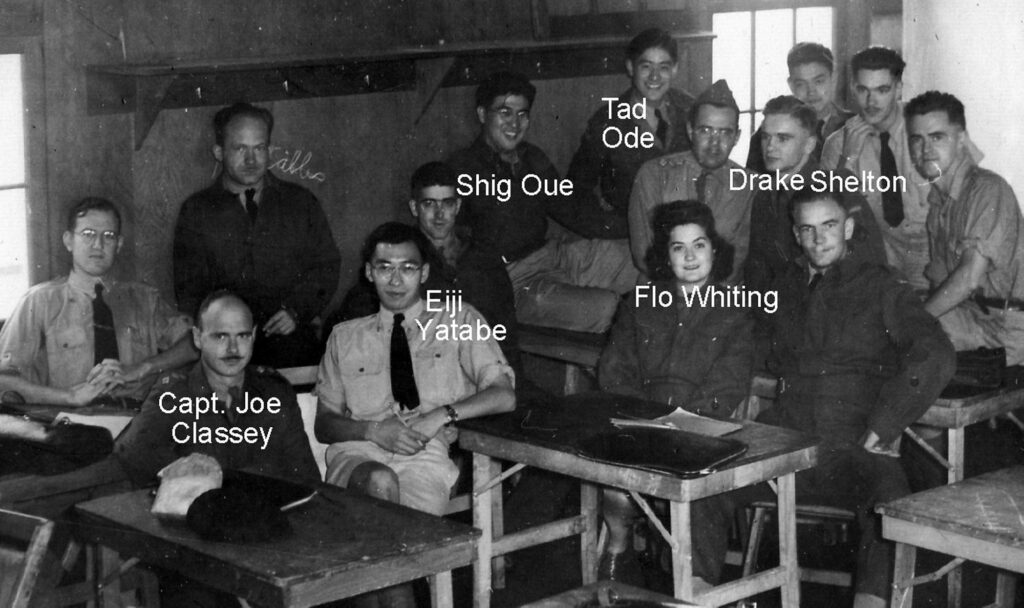

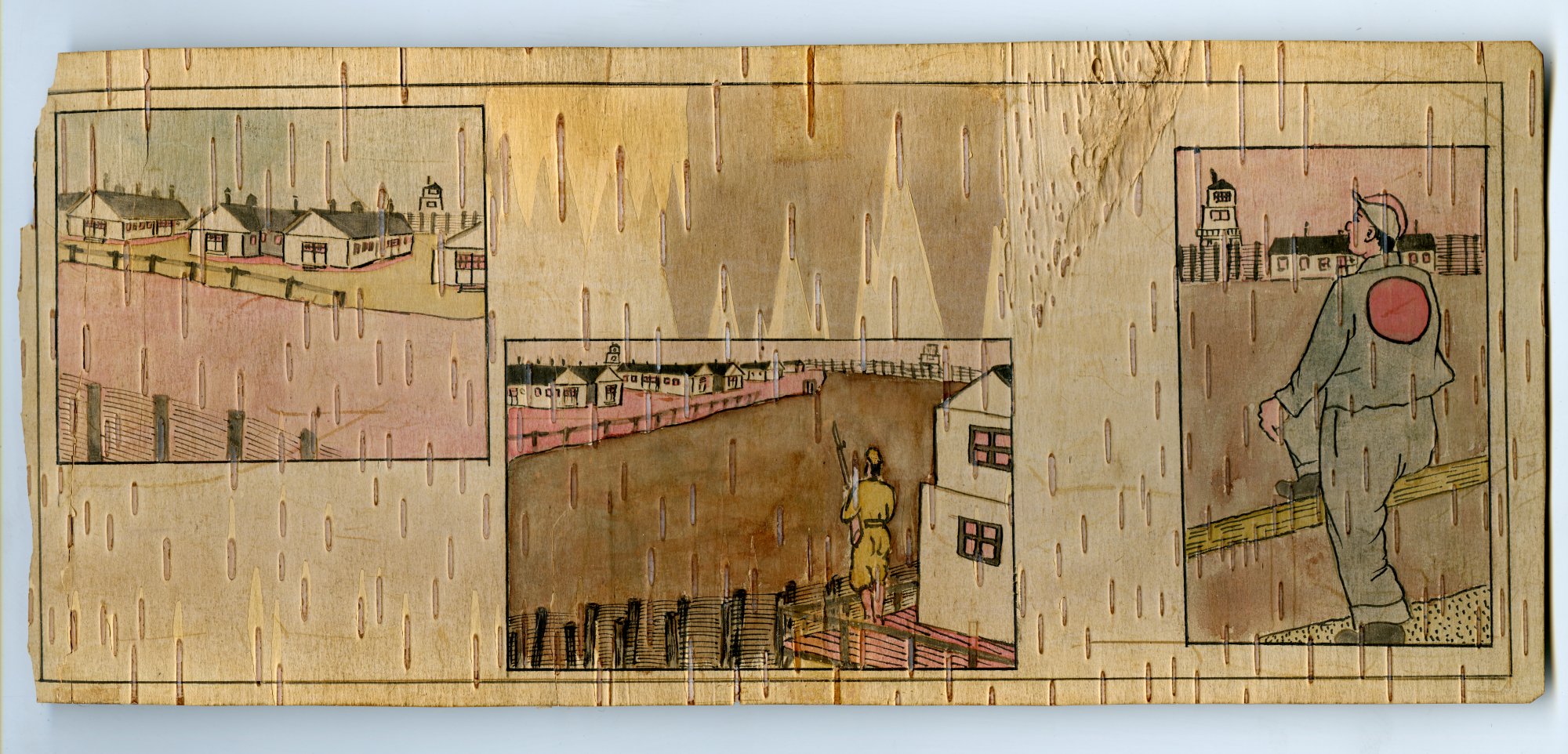

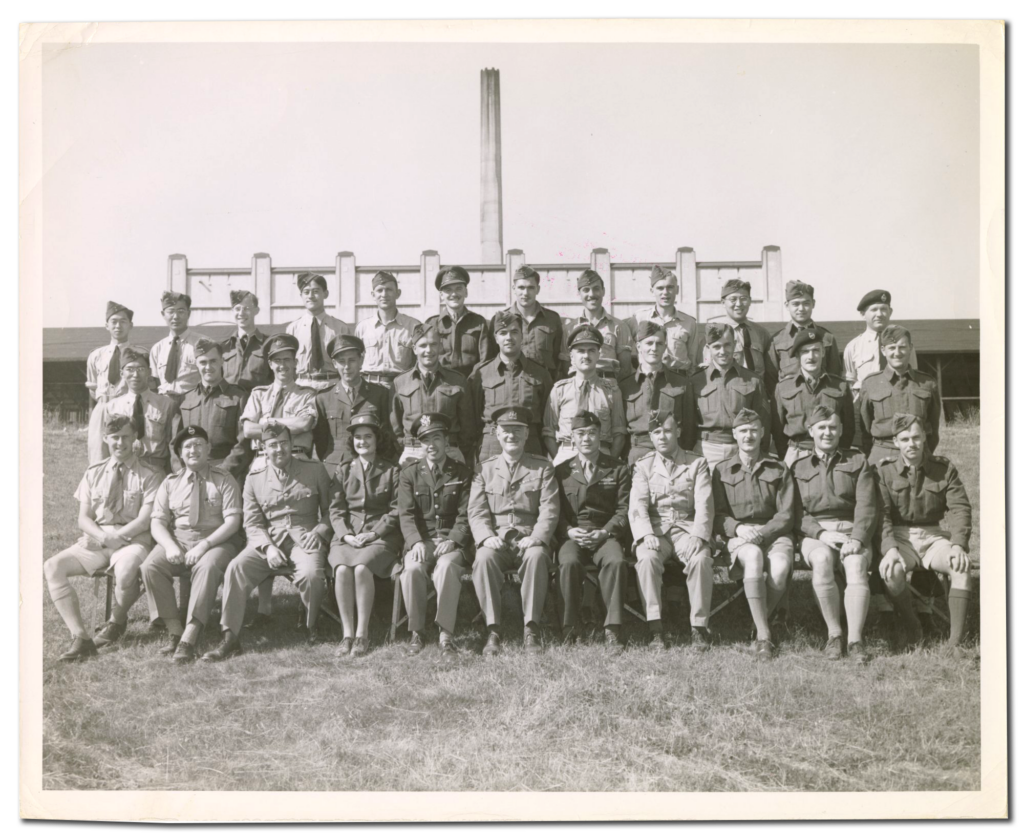

Front Row: (2) “Wimp” Tomlinson, (3) Captain McTavish, (4) Flo Whiting, (5) Ted Kihara (from US), (6) Arthur McKenzie, (7) Dye Ogata (from US), (9) Joe Classey.

Second Row: (1) Eiji Yatabe, (5) Drake Shelton, (9) Bill Hunter.

Third Row: (1) Roy Ito, (2) Sadao Nikaido, (3) Frank Haley, (8) Ferdnand Leduc, (10) Shig Oue, (11) Tad Ode. Identifications courtesy of Dr. Frank Haley. Roy Ito Collection. NNMCC 2001.4.4.5.8.

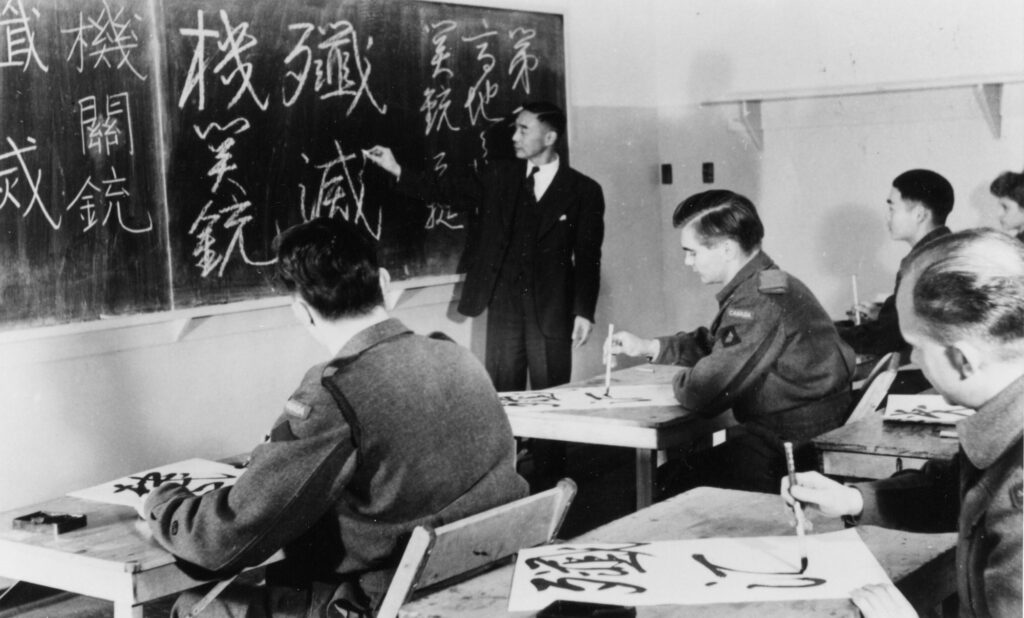

In August 1943 the S-20 Canadian Army Japanese Language School opened at Vancouver. The school was created by Lt-Colonel B.R. Mullaly, formerly an ex-British Army officer who had settled in Victoria. He worked as an intelligence officer with Pacific Command (LaMarsh, 1967). Major Arthur McKenzie arrived early in 1944 to serve as the commanding officer of the school. He had served as an Intelligence Officer in France in the First World War and lived in Japan after the war (Ito, 1984, p. 214).

The school was moved to four different locations in Vancouver (LaMarsh, 1967) between its creation in 1943 to its official closure in July 1946.

Before nisei arrived at the language school, there were already eighty non-Japanese students who had been enrolled at the school for nine months. Many of them became famous years later, including Arthur Erickson, architect; Judy LaMarsh, Secretary of State; William Sommerville, president of the Canadian Bar Association; Hugh Stephen, mayor of Victoria, BC.; and Saul Cherniak, Manitoba cabinet minister (Ito, 1984, p. 214). Two instructors were Canadian nisei; two were nisei on loan from the US Army. The nisei arriving from Brantford were very impressed with the progress that the eighty students had already made in nine months at S-20. The nisei students found interrogation classes easy, but had no prior experience with Japanese military and technical terms.

Left to right: Eiji Yatabe, Roy Ito, Shigeru Oue, Tad Ode, Sadao Nikaido.

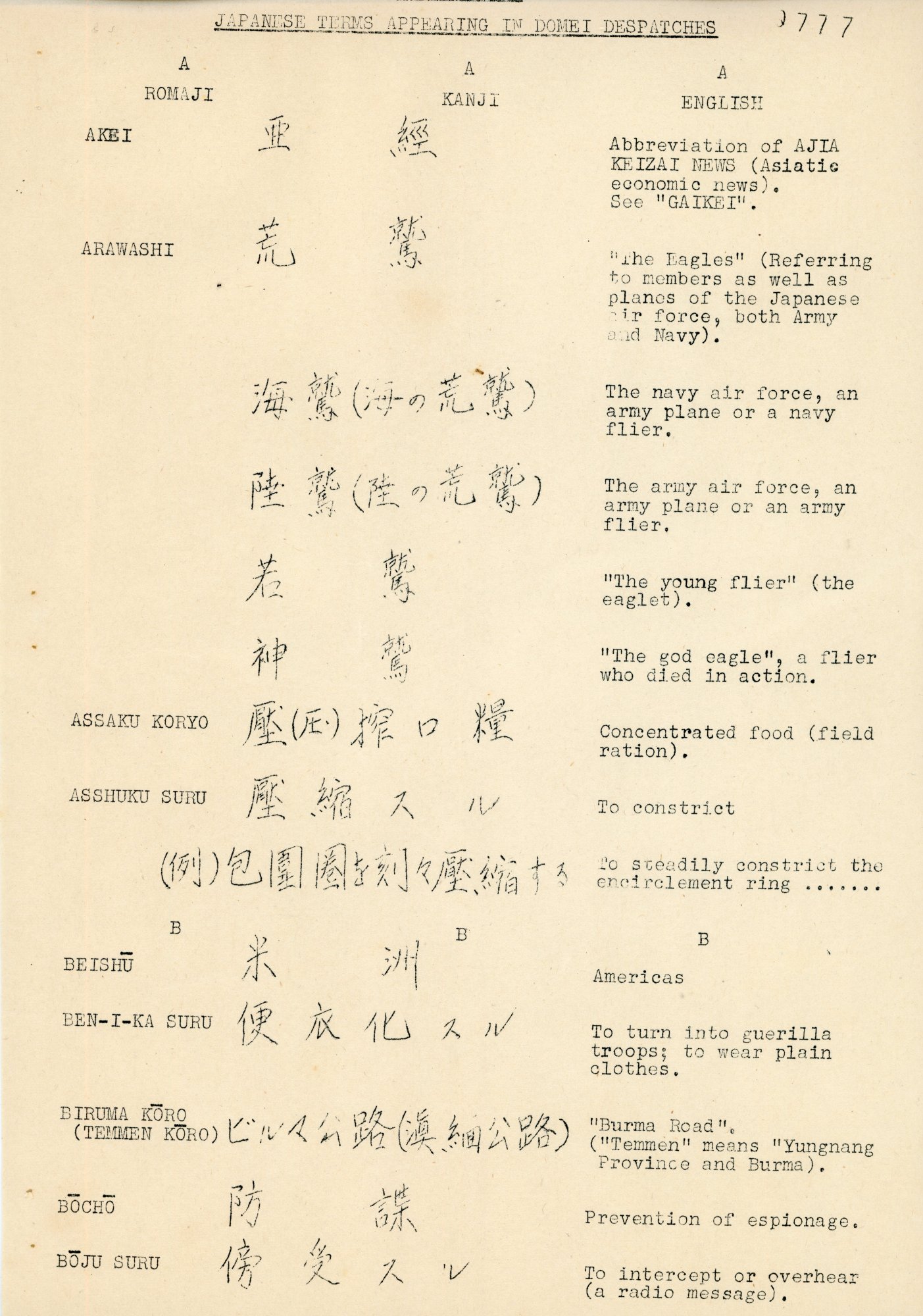

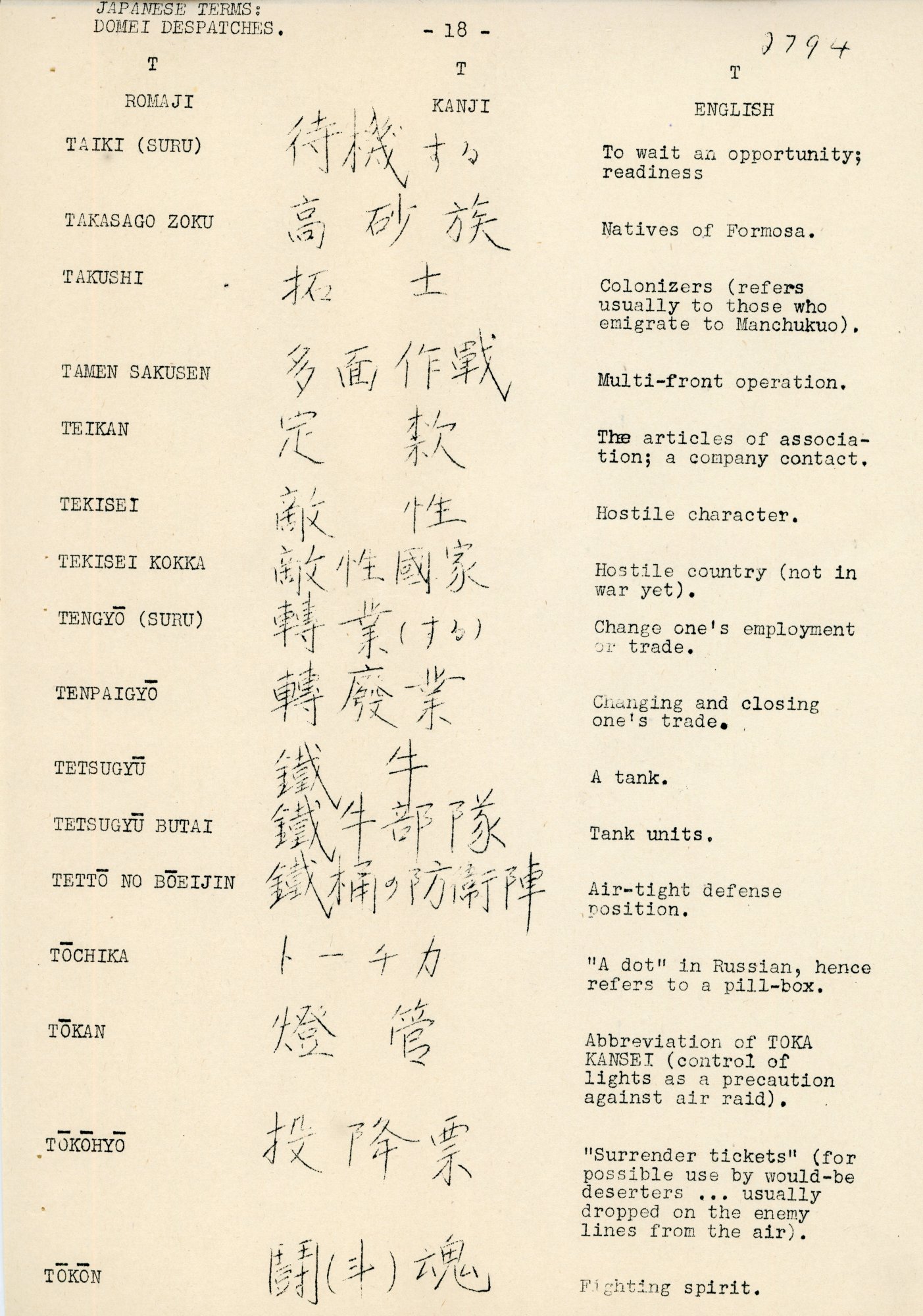

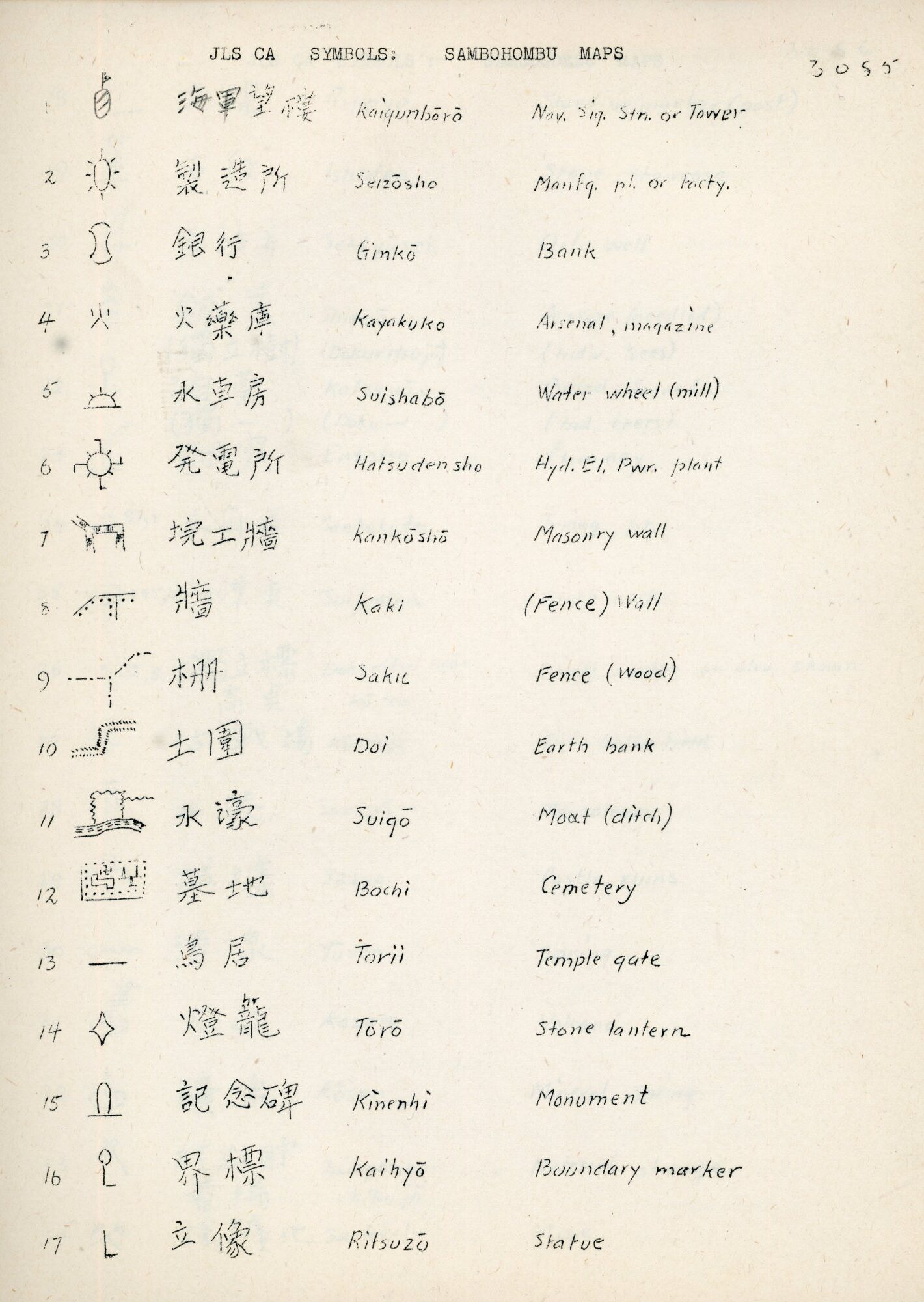

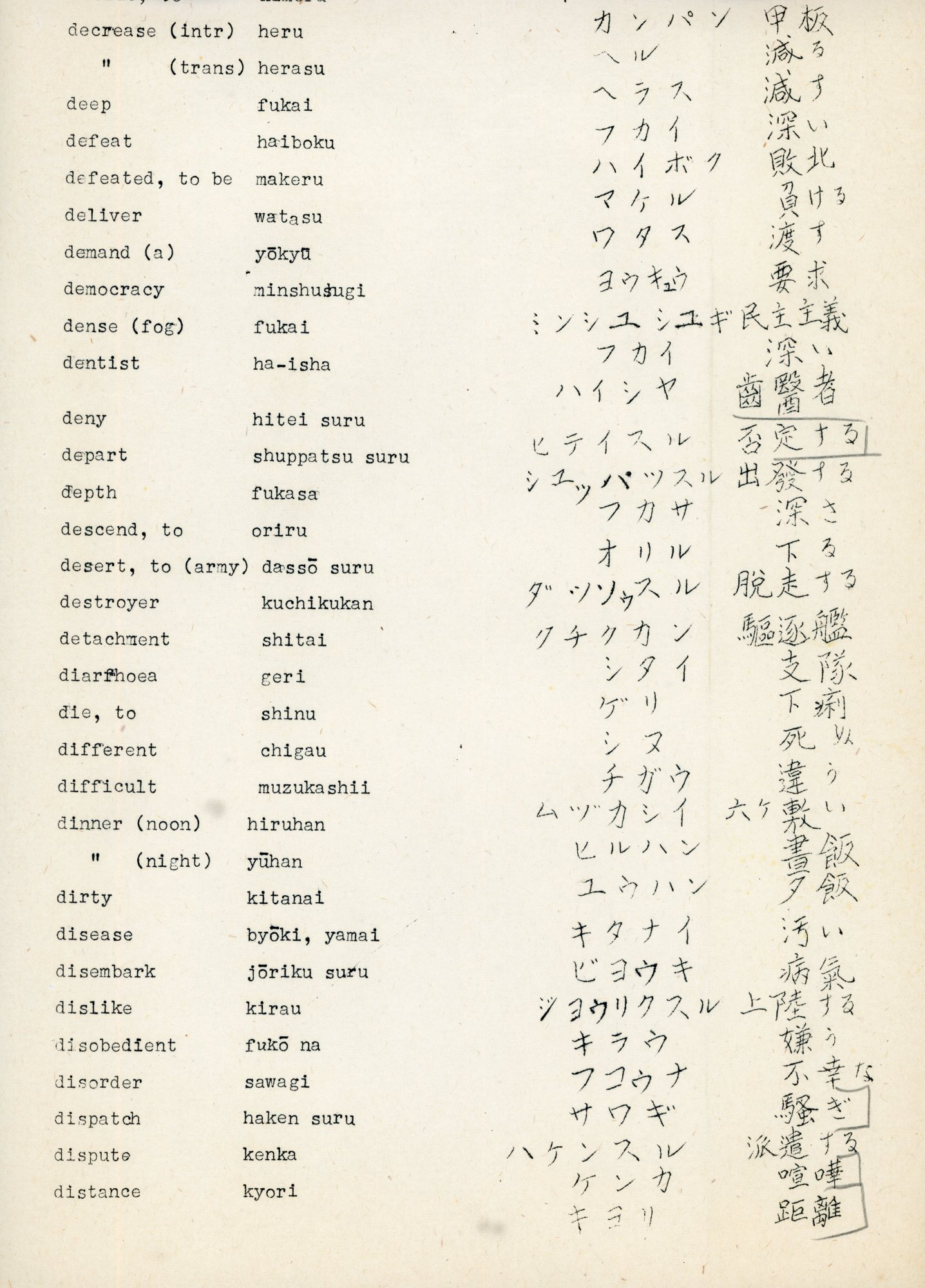

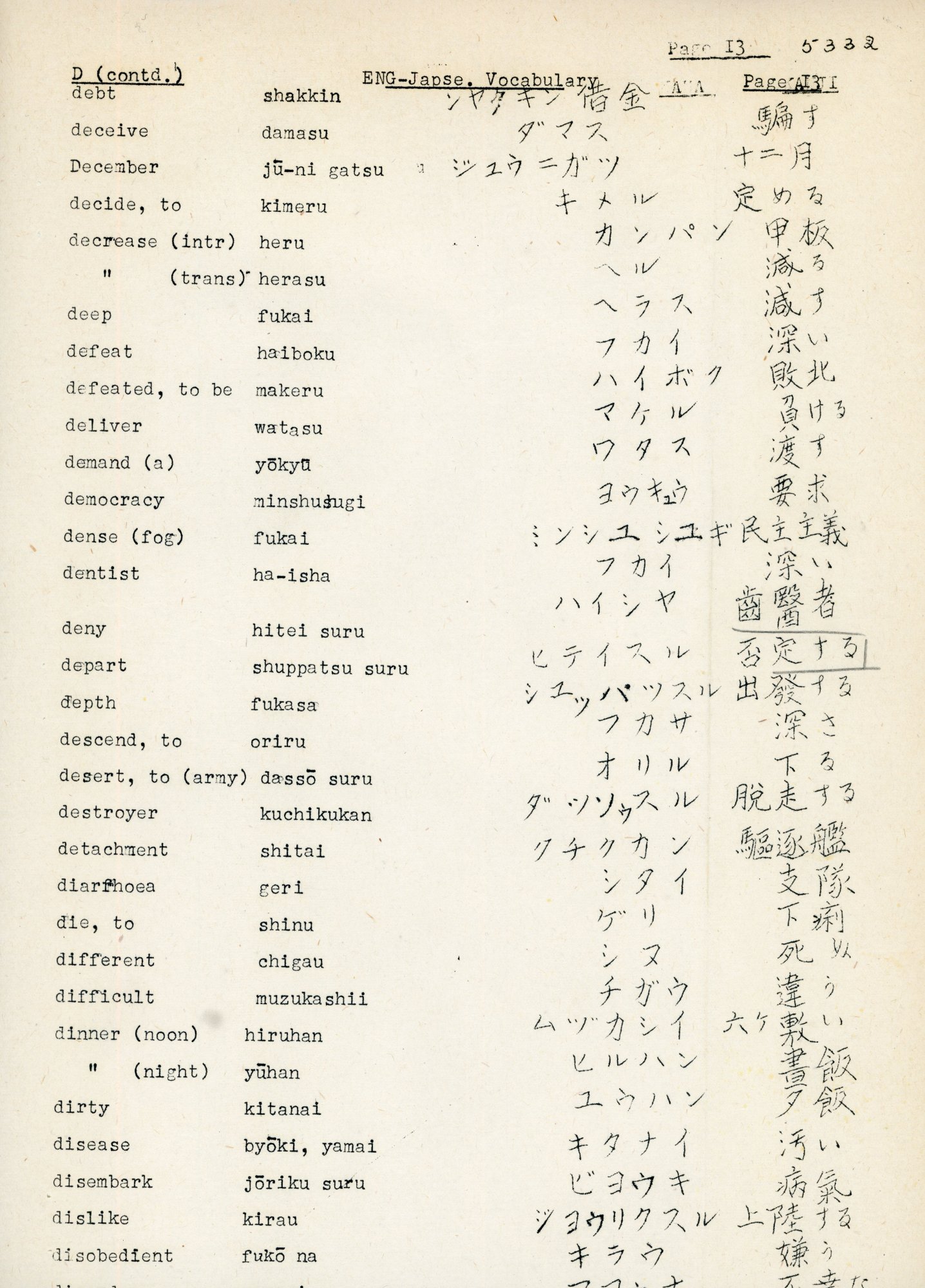

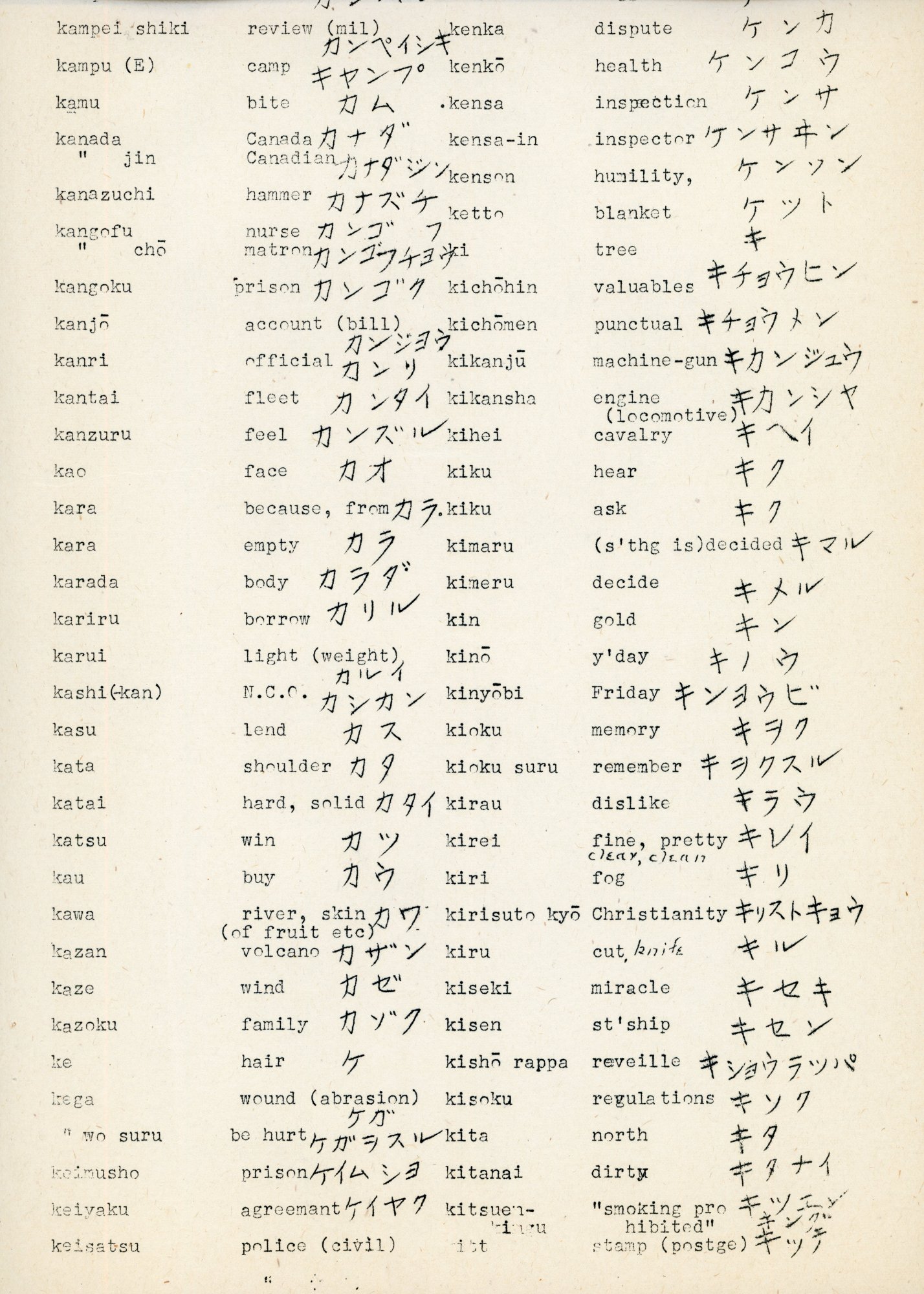

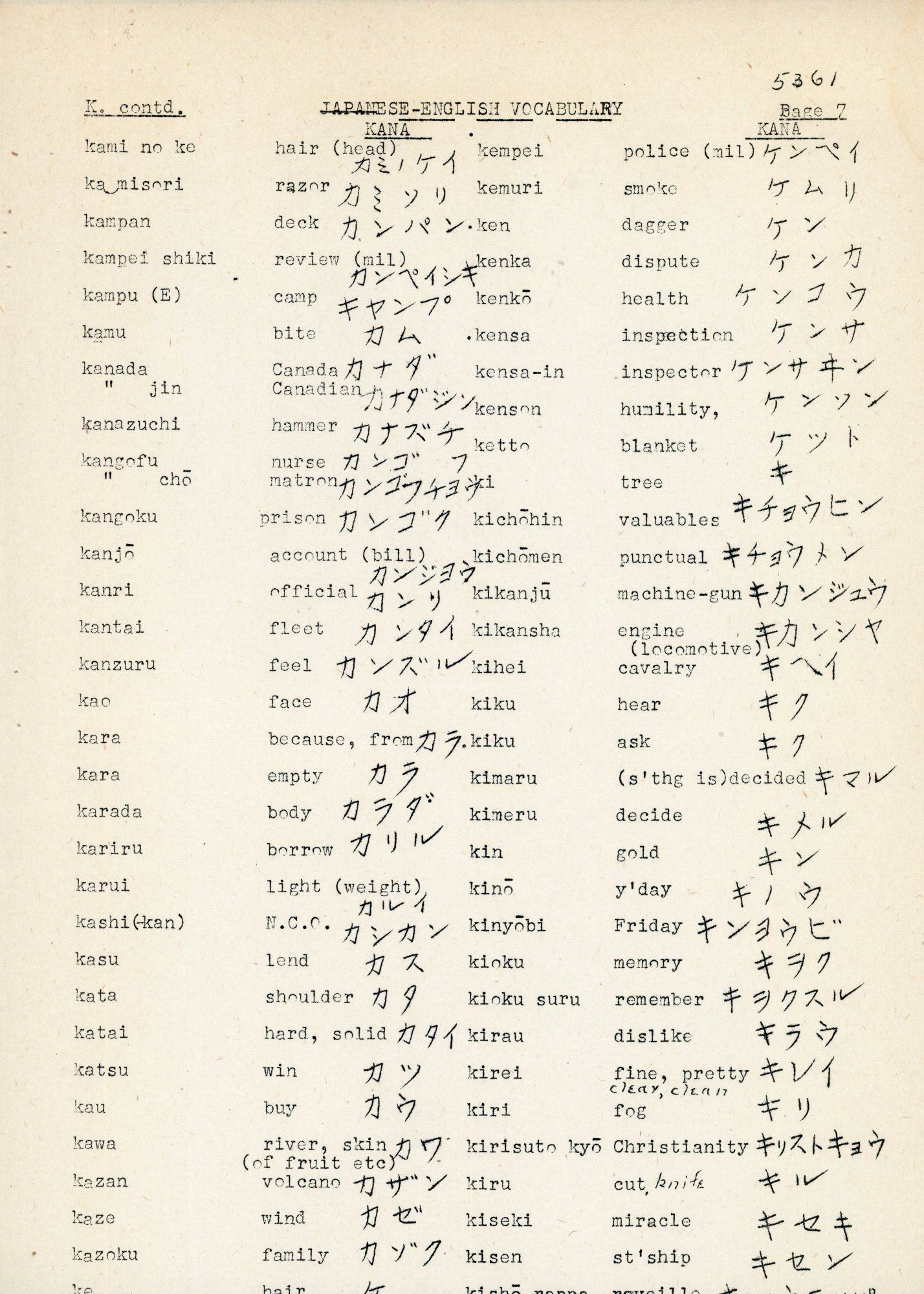

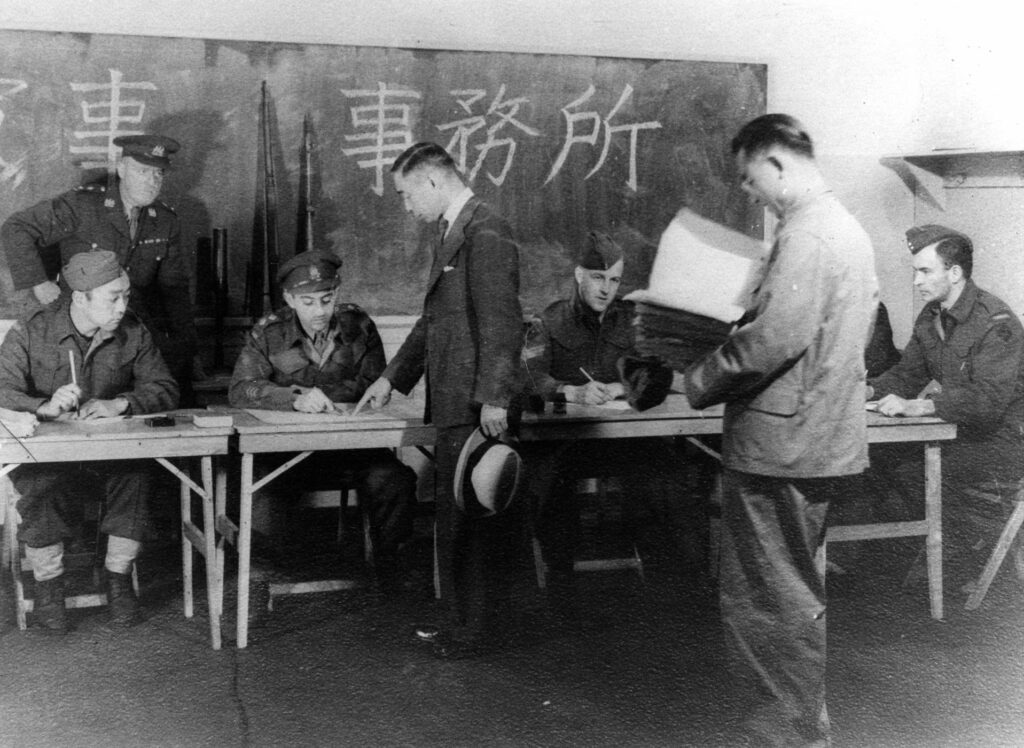

The one-year curriculum that the eighty original students had studied began with an introduction to the Japanese language (reading and writing), culture, and geography. Oral exercises became increasingly focussed on military subjects. Students learned to read military terms, maps, and expressions in kanji. They learned to recognize Japanese military signs and abbreviations. They studied POW interrogations. Emphasis was on correct pronunciation of kanji, fluent reading of texts, and writing of kanji that had been learned in classes. Students translated captured Japanese documents and diaries of Japanese officers, which gave them insights about Japanese tactics and weapons, terminology, and inadequacies (Ito, 1984, p. 219). They also listened to Japanese radio broadcasts intercepted by Allied monitoring stations (Ito, 1984, p. 220).

Japanese-English Vocabulary, S-20 Training Documents of Stum Shimizu, circa 1945. Stum Shimizu Collection. JCCC 2007.22.03.03. Glossary of Japanese terms appearing in Domei dispatches, S-20 Training Documents of Stum Shimizu, circa 1945. Domei was the official news agency of the Empire of Japan. Stum Shimizu Collection. JCCC 2007.22.03.03.

The nisei arriving from Brantford were placed in the S-20 school after missing the first nine months of an already advanced Japanese language course (Sedai interview, August 16, 2010, JCCC, 58:40). The course was very difficult and resulted in some nervous breakdowns among students (Ito, 1984, p. 243).

On August 2, 1945, the six nisei in the senior class at S-20 were officially posted to the Canadian Army Pacific Force, and were about to begin training at Fort Breckenridge in the US for the final assault on Japan. Four days later, the atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima, and seven days later, another bomb fell on Nagasaki. On August 14, the Emperor of Japan ordered Japan to surrender. The S-20 students and staff gathered around the flagpole at the school to mark the end of the war (Ito, 1984, p. 223).

“The long war that had completely destroyed the Japanese community and scattered its people across Canada had come to an end. At S-20 there was no jubilation, no shouting, no expressions of joy; the nisei had mixed feelings. There was relief that the war was over, but with mixed feelings of horror and revulsion, a sharper understanding of the utter obscenity of war. One atom bomb could indiscriminately kill thousands of men, women and children (Ito, p. 1984, p. 224)”.

There was no longer a need for the Canadian Army Pacific Force to take to the field with Japan (Ito, 1984, p. 222, 223), but there was still a requirement for Japanese language speakers to engage with surrendered soldiers in southeast Asia and to assist with the occupation of Japan.

The six nisei in the senior S-20 class graduated at the end of September, having completed their one-year Japanese language course in approximately two months. The six were Roy Matsui, Shig Oue, Eiji Yatabe, Sadao Nikaido, Tad Ode, and Roy Ito. Their commanding officer, Mackenzie, recommended that three be commissioned and three be promoted to warrant officer, second class, but all of the graduates, nisei and non-Japanese, were promoted to sergeant. By 1947, all of the nisei in the senior class would be promoted to warrant officer or staff sergeant (Ito, 1984, p. 224).

Some of the nisei recruited for the S-20 became prominent community leaders who continued for years to advocate for the rights of Japanese Canadians.

The second and final overseas draft of nisei from S-20 left Vancouver in January 1946 for Singapore via England and India. The S-20 school was moved to Ambleside Camp in West Vancouver later in 1946. Two incidents upset the commanding officer of S-20 because they resulted in unwanted publicity and attention on the intelligence unit and the nisei students. Roy Matsui recalled this incident 64 years later (Sedai interview, August 16, 2010, JCCC, 1:00:00).

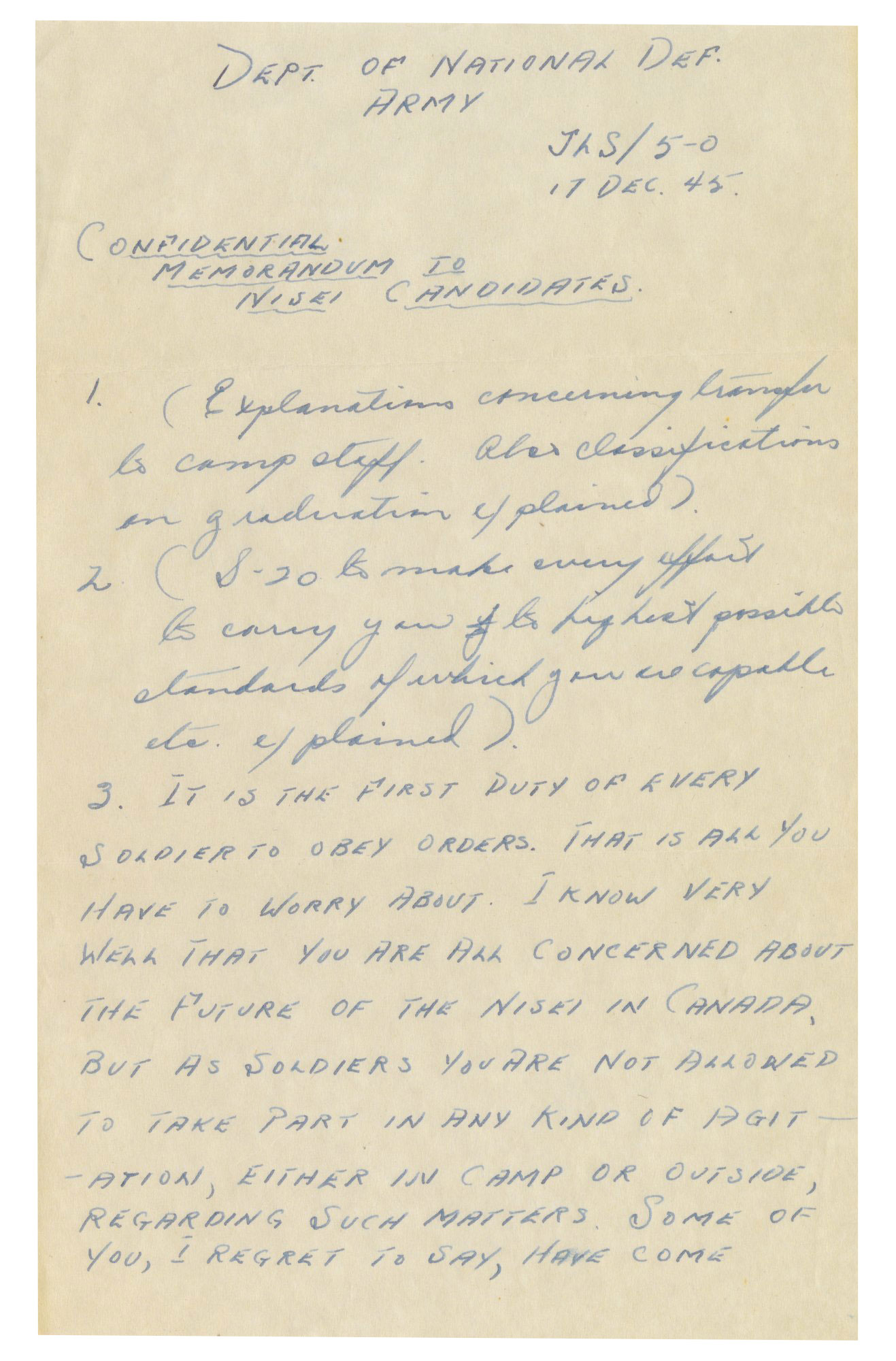

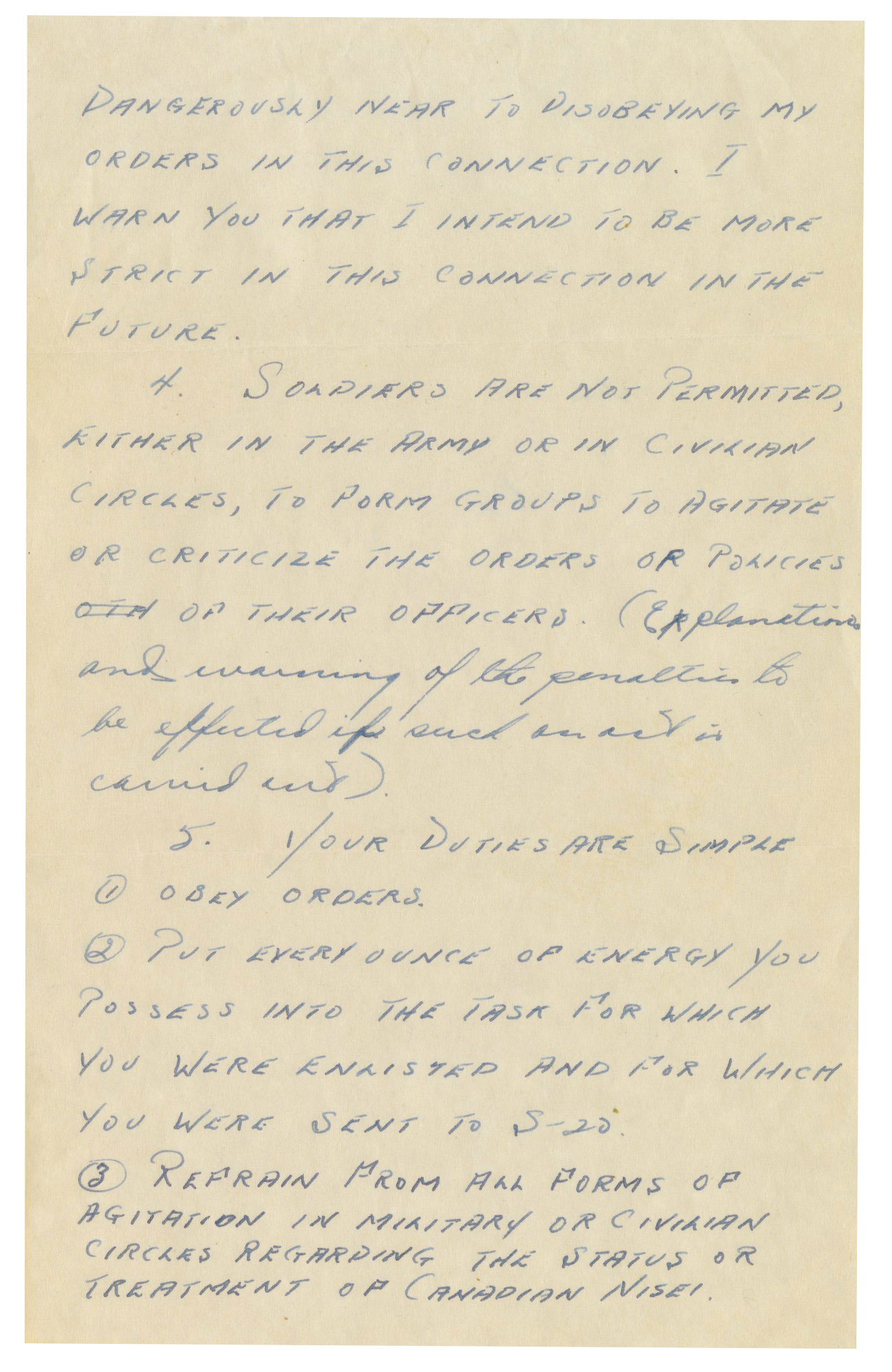

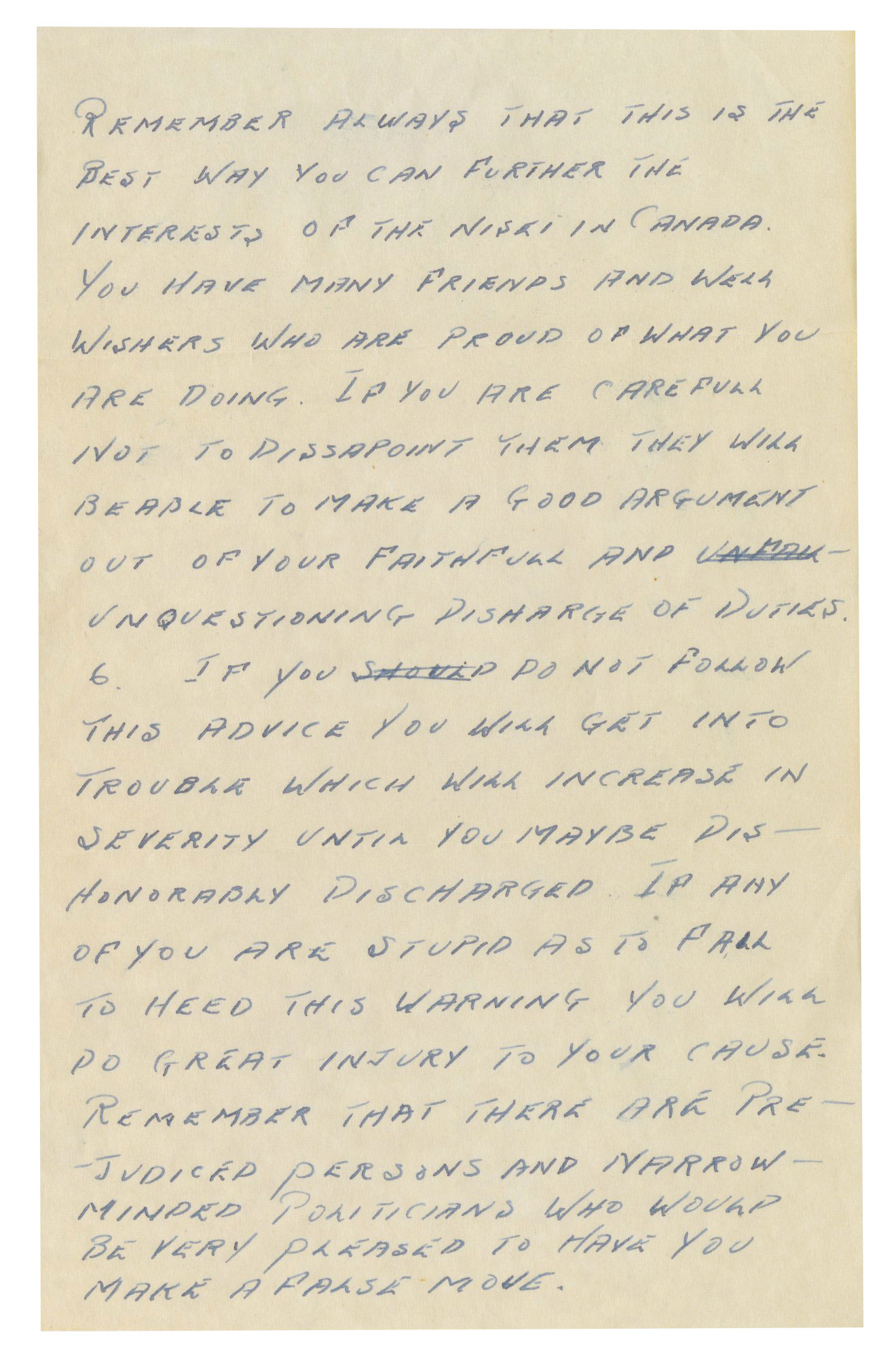

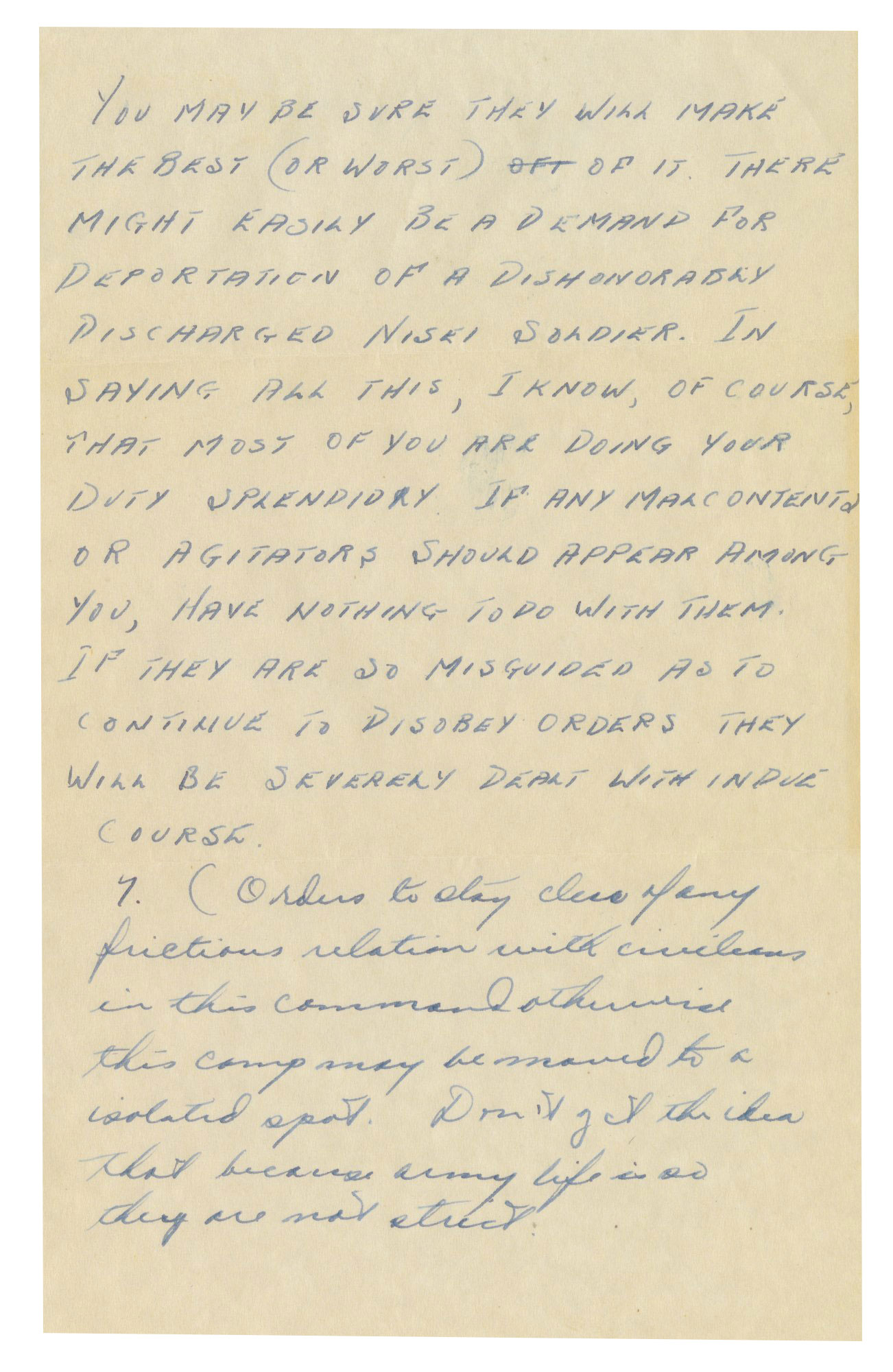

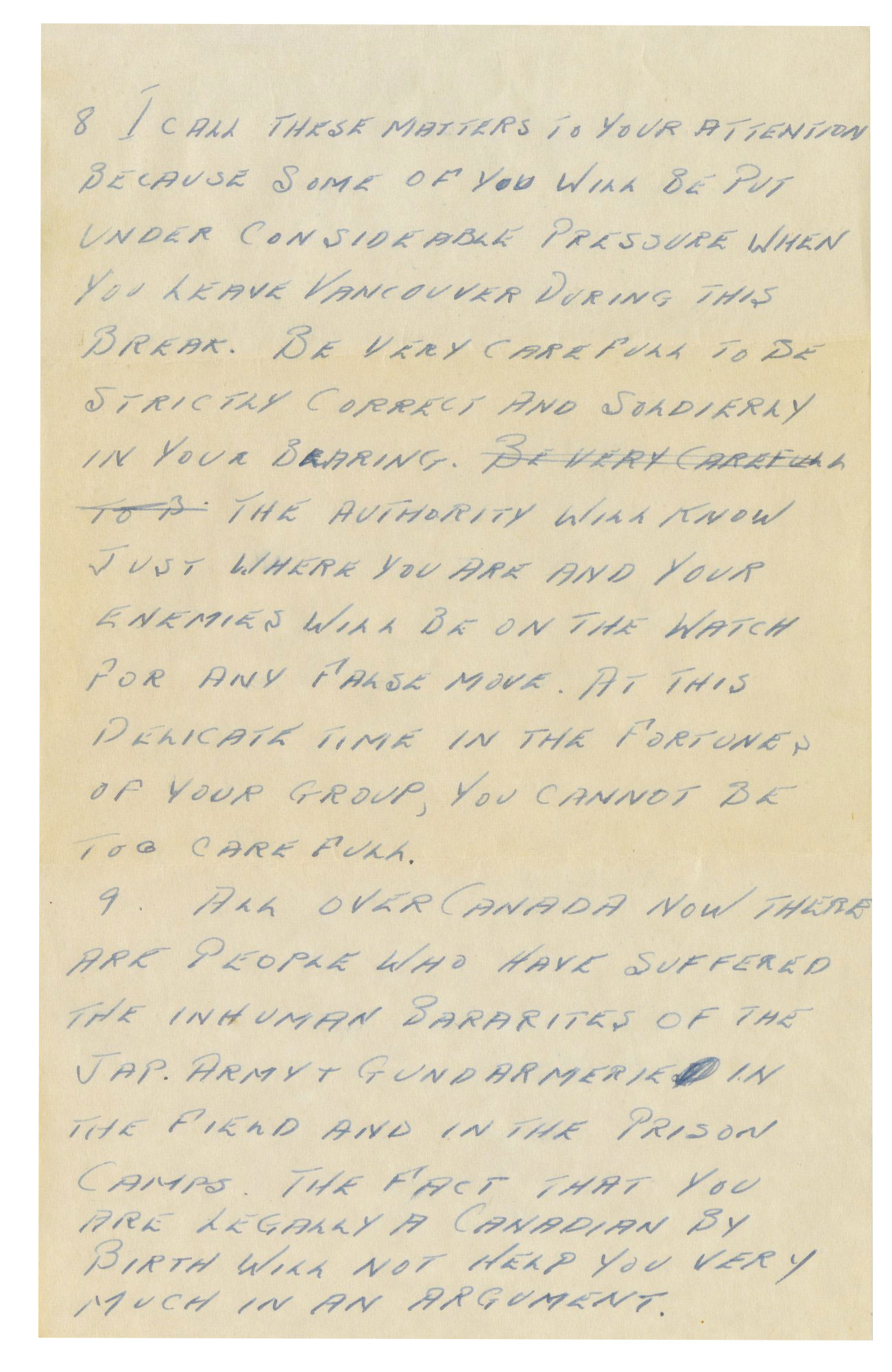

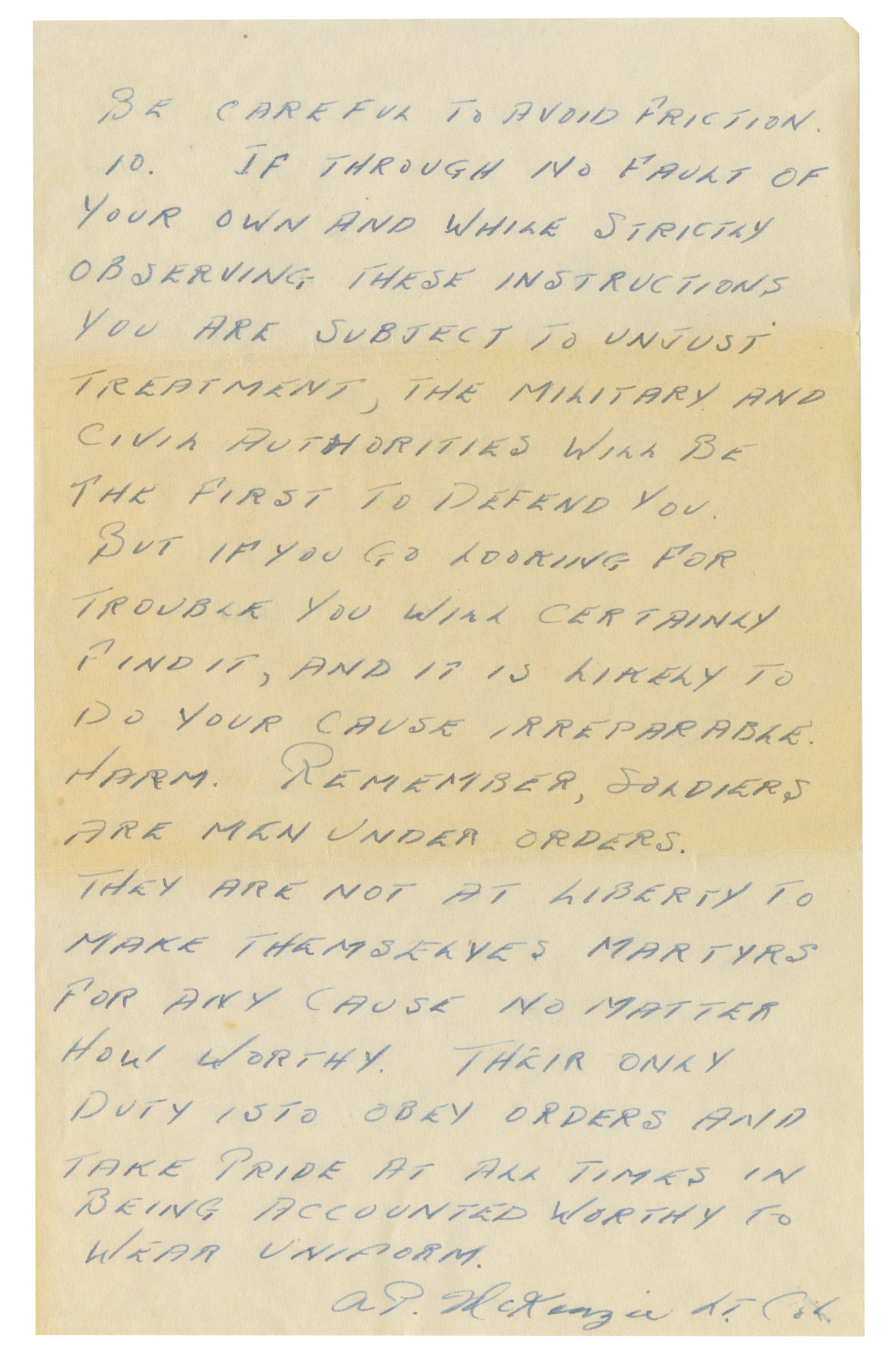

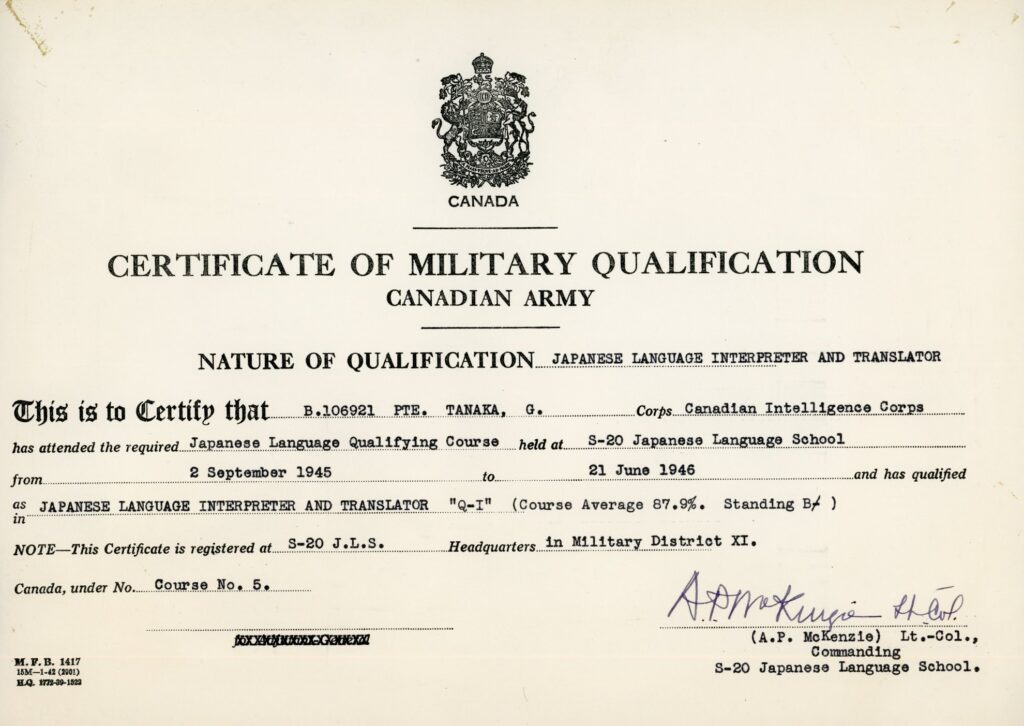

In the first incident, George Tanaka, Roger Obata, and Tom Shoyama were invited by one of their instructors to attend a meeting in which the subject of sending all Japanese “back to Japan” was being discussed. Tom Shoyama argued with some of the people in the meeting, defending the New Canadian newspaper. The meeting was recorded on the radio and was publicized in the local newspaper. The three nisei were reprimanded. In the second incident, an S-20 nisei student, David Watanabe, was refused entrance to a theatre because the manager did not allow Japanese to be admitted. The manager called the police; the police explained that Watanabe had not committed any crime, and drove the soldier back to the S-20 school. The nisei were told by the camp to stay away from the theatre. Angry about this discrimination and lack of support from their superiors, several nisei tried several days later to enter the theatre and were again refused. Again, the commanding officer of S-20 was upset at the attention focused on the school and he issued a letter to the nisei that demonstrated his anger (Ito, 1984, p. 224-231). Veteran Bill Sasaki had the original copy of Major McKenzie’s letter.

Letter from Lt.-Col. McKenzie to S-20 Nisei students; 17 December 1945. Courtesy of Elaine Keating.

Just two drafts of qualified nisei graduates from S-20, totaling 120, saw overseas service. Forty-eight of 62 nisei enlistees completed the S-20 course. Sixty-one nisei served in India, Southeast Asia, Australia, Japan, Washington, and Angler, Ontario (Ito, 1984, p. 232). Three nisei, left at S-20 with no prospect of going overseas as the war needs no longer existed, travelled to Washington D.C. to enlist for US. Occupation Duty in Japan but were unsuccessful (Oki, 1967).