The Asiatic Exclusion League had been formed in 1907 by the Vancouver Trades and Labour Council (Mussett, undated).

“The object of this organization is to work for the exclusion from the Dominion of Canada, its territory and its possessions, all Asiatics by the enforcement of an act similar to the Natal act,” said a story in the anti-Asian newspaper, the Vancouver World, on Aug. 10, 1907. “The list of signatures was headed by Mayor Bethune, and includes several members of the legal legislature and a member of the Dominion parliament (Mackie, 2017).”

The League insisted that Asian immigration threatened the jobs of white workers because Asians accepted lower wages. Frequent mentions were made of Asians having a lower standard of living than white Canadians and being unable to assimilate into Canadian society; the language schools and Japanese associations were evidence of this failure to assimilate. Allowing Asians to raise their standard of living was also apparently a threat. The objective of the League was to keep Asian immigrants out of British Columbia.

“To counteract the debilitating effects of their lower wage, Asians worked longer hours and had higher productivity than their white counterparts. To the labour agitators, compensating for a low wage with high productivity was an unfair tactic. Damned for having a lower standard of living and damned for working hard in order to raise it, Asians were locked into a double standard (Sunahara, 2000, page 7)”.

“Japanese Canadians were feared by whites because they worked too hard and were too intelligent to remain contented as labourers (Ito, 1984, page 86)”.

The Japanese were seen as not just an economic threat. The Vancouver Sun said “the yellow peril is not the yellow battleships nor yellow settlers but yellow intelligence (Theurer and Oue, 2021)”.

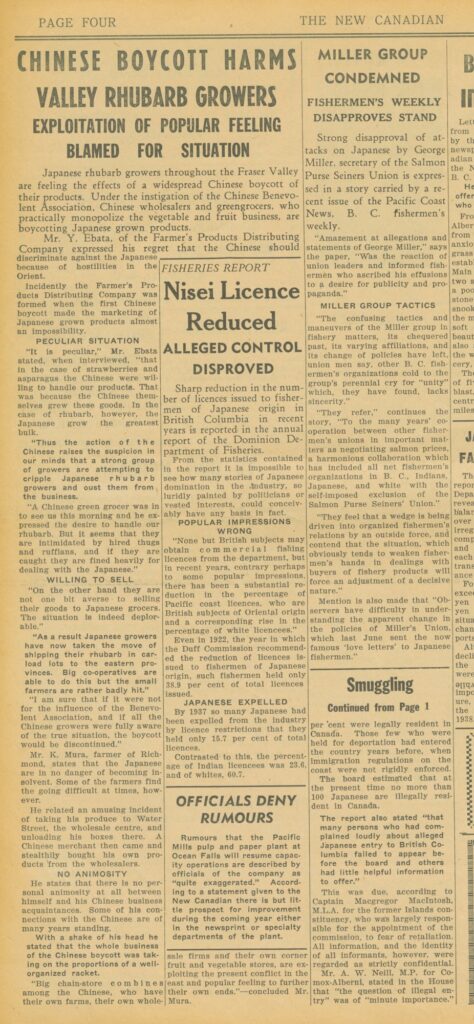

In 1919, Japanese Canadian fishermen owned nearly half of the fishing licenses (3,267). The Department of Fisheries began to reduce the number of licenses issued annually to people “other than white residents, British subjects and Canadian Indians”. By 1925, approximately 1,000 licenses had been removed from Japanese Canadians through the orders of politicians such as A. W. Neill. Japanese had been prevented from using motorized boats on the Skeena River until an issei fisherman, Jun Kisawa, won a legal battle in 1929 to overturn this restriction (Greenaway, 2012).

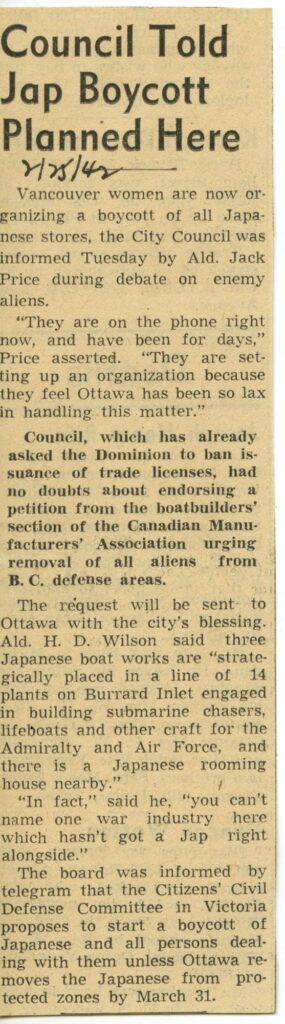

Politicians in British Columbia fanned the flames of anti-Japanese sentiment. Vancouver Alderman Halford Wilson gave many speeches and interviews on the theme of “the Oriental menace”. His father had been one of the chief instigators of the 1907 anti-Asian riots (Tamaki, 1940). Wilson (the son) restricted trade licences to Japanese Canadians, tried to cancel the licences of nikkei fisherman, and expounded constantly on the threat of Japanese Canadian penetration into the provincial economy and the danger that by 1968 the Vancouver school population might explode to including one-third Japanese Canadian students.

“He exploited Japanese Canadians for his own political advancement and became the No. 1 anti-Japanese agitator. As a public servant, his efforts were wholly incompatible with his responsibilities. He left a crimson trail of ignominy behind him (Adachi, 1953, page 2)”.

Halford Wilson criticized nisei who went to Japan after finishing school in Canada as a waste of taxpayer’s money. The nisei didn’t go to Japan by choice, but there were no opportunities for them in Canada because they were unable to work in most professions.

“A nisei would never be considered for work as a postman, a fireman, a policeman, a salesperson in a white store, work in city hall or any office in the city, a teacher, a nurse, a conductor on streetcars. No nisei was able to obtain a position in municipal, provincial, or federal services. No companies hired nisei, no stores hired nisei…Worried parents saw no future for their children in Canada, and some, with hope, sent their offspring to Japan (Ito, 1994, page 169)”.

Opposition among BC Legislature Members to granting the franchise to Japanese Canadian First World veterans was explained as follows:

“The Japanese had a lower standard of living, and thus it was undesirable for Japanese children to mix with other children. Although they recognized the fact that the Japanese veterans had rendered great service to Canada, they were not willing to grant them the franchise (Shinobu, 1931).”

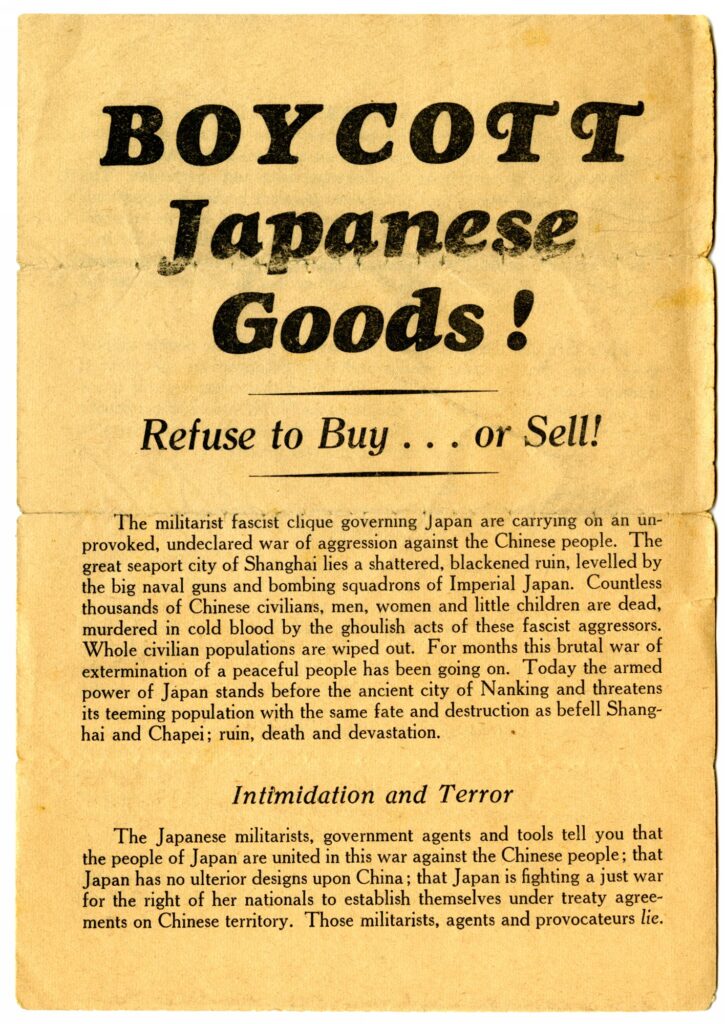

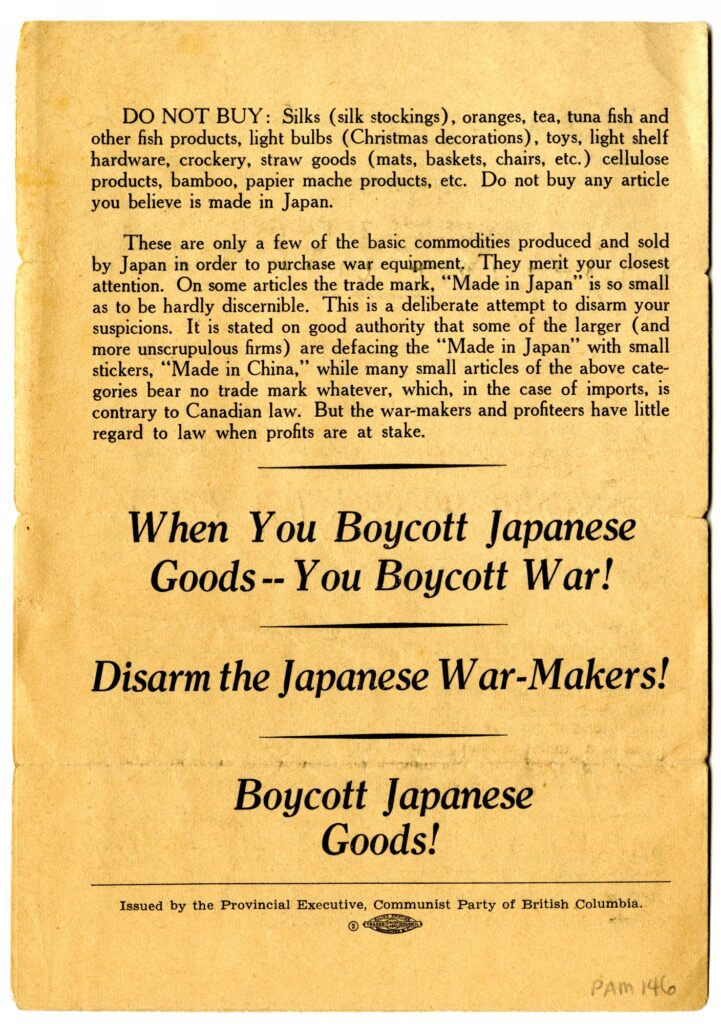

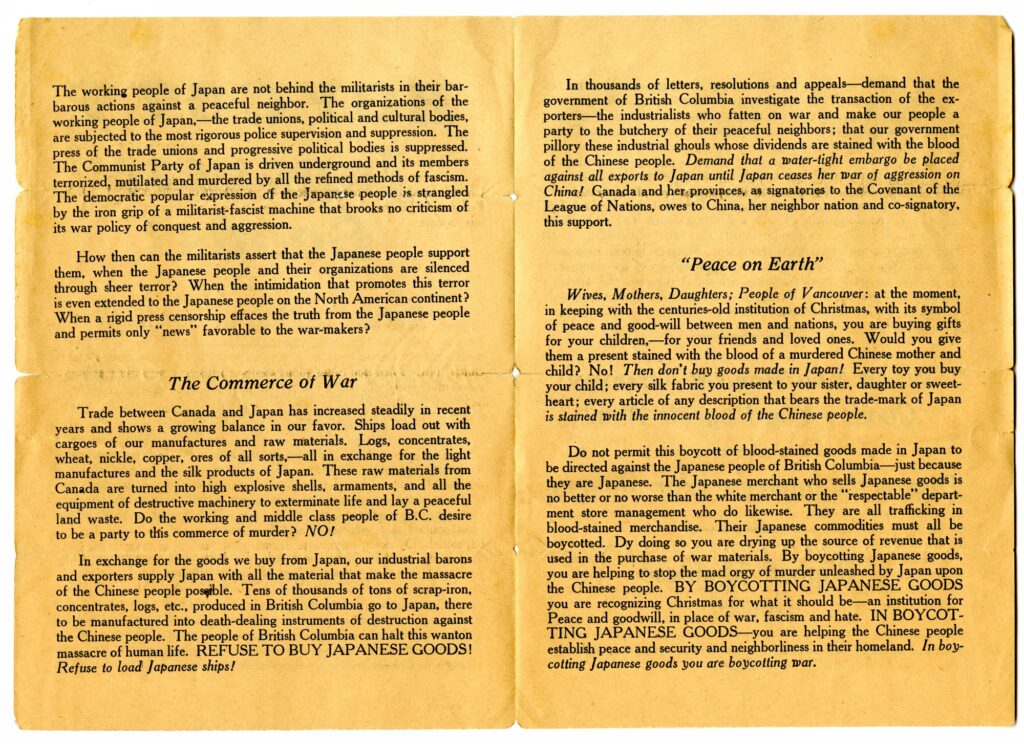

Once atrocities committed by Japan in China became public knowledge, Canadians on the west coast became increasingly suspicious of Japanese Canadians. In Vancouver, there were boycotts of Japanese and Japanese Canadian products and loud anti-Japanese demonstrations in British Columbia.

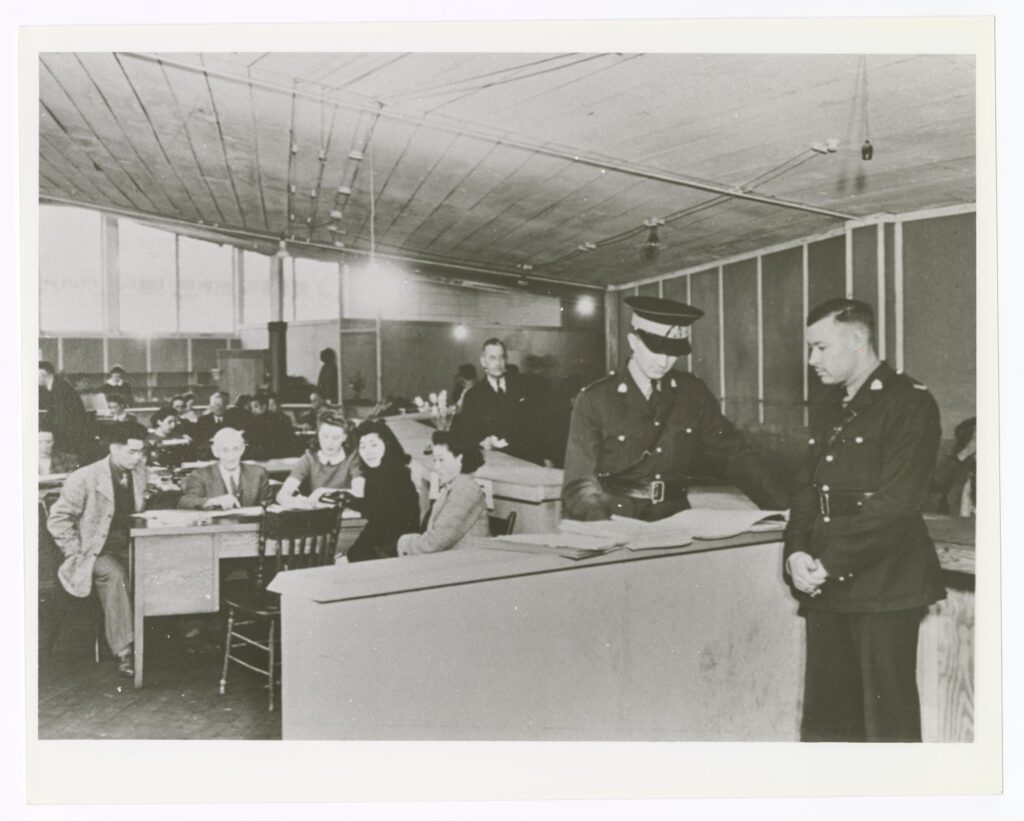

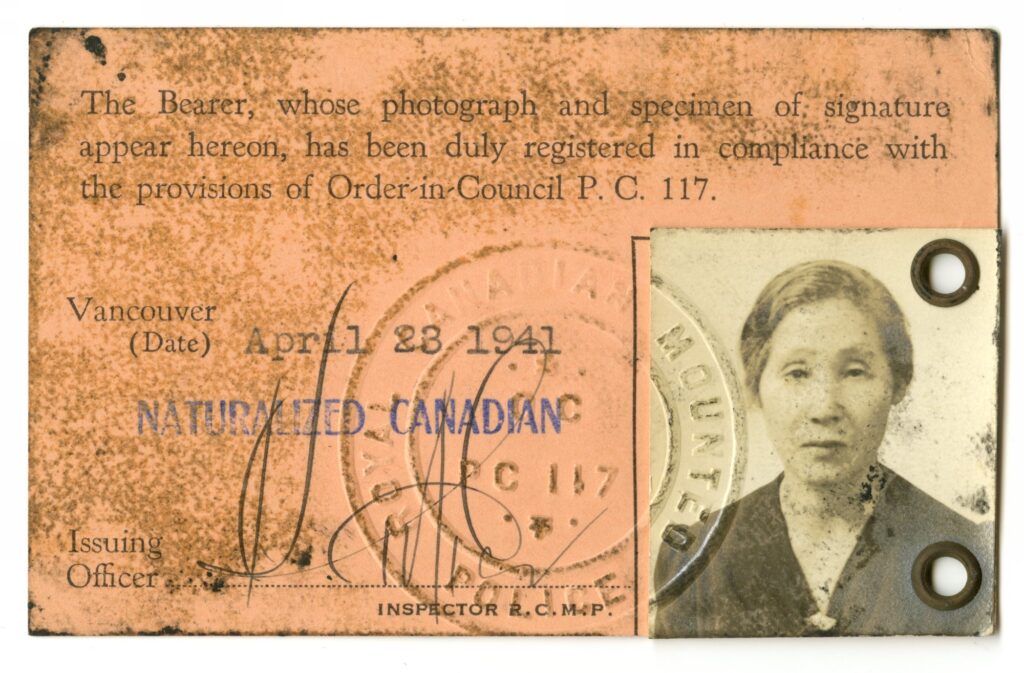

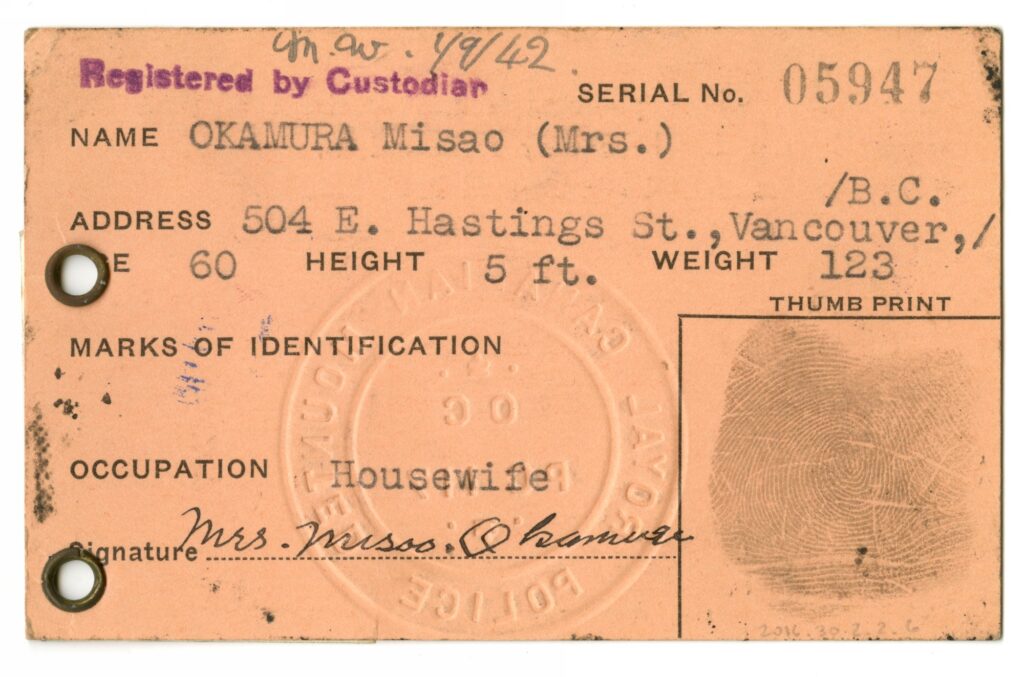

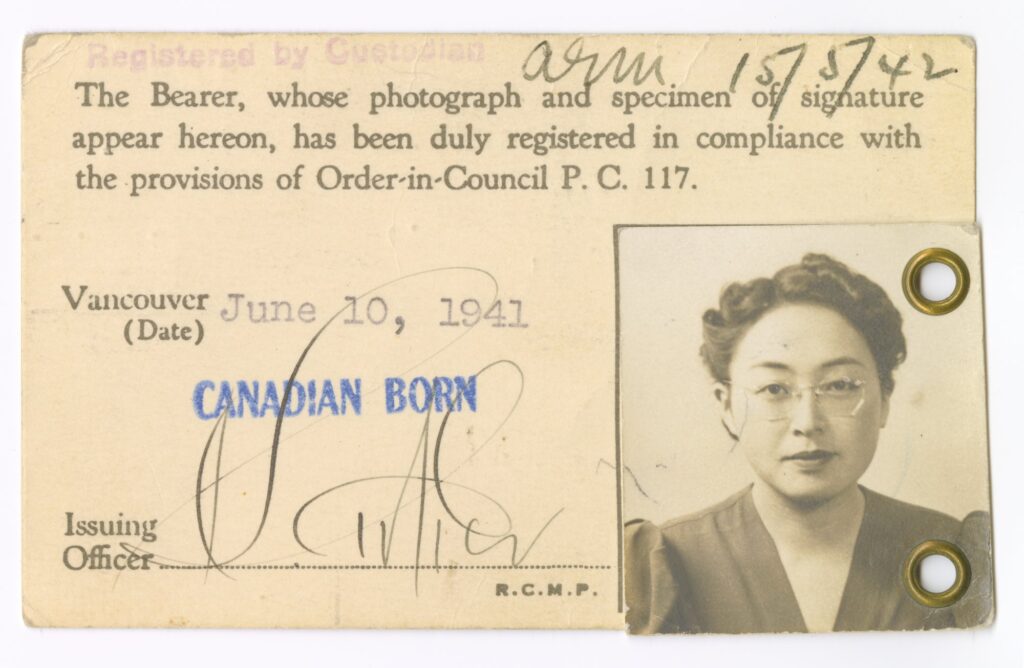

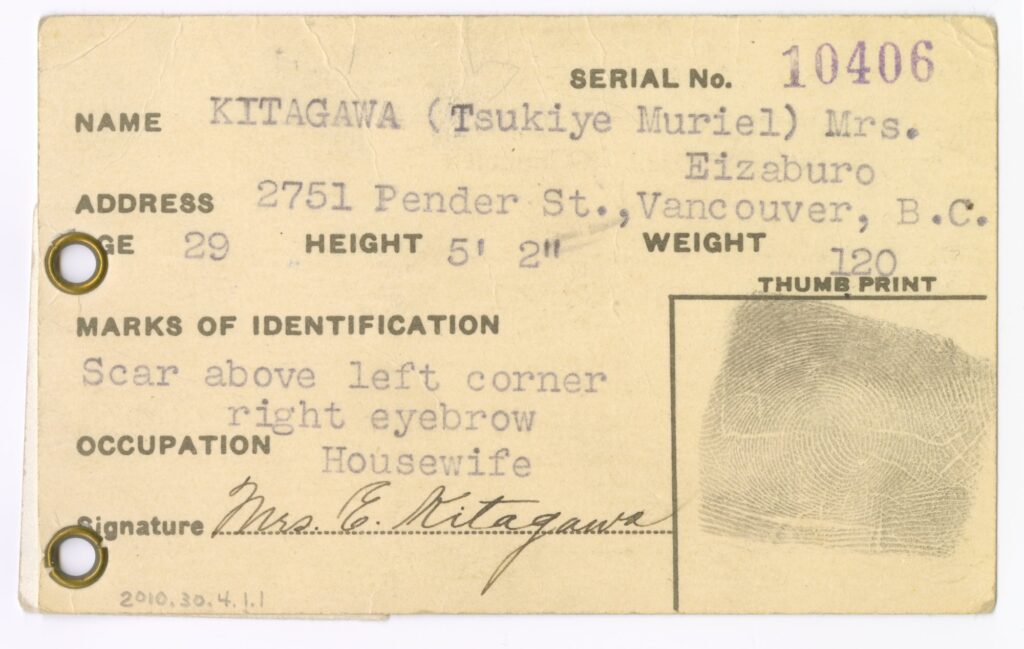

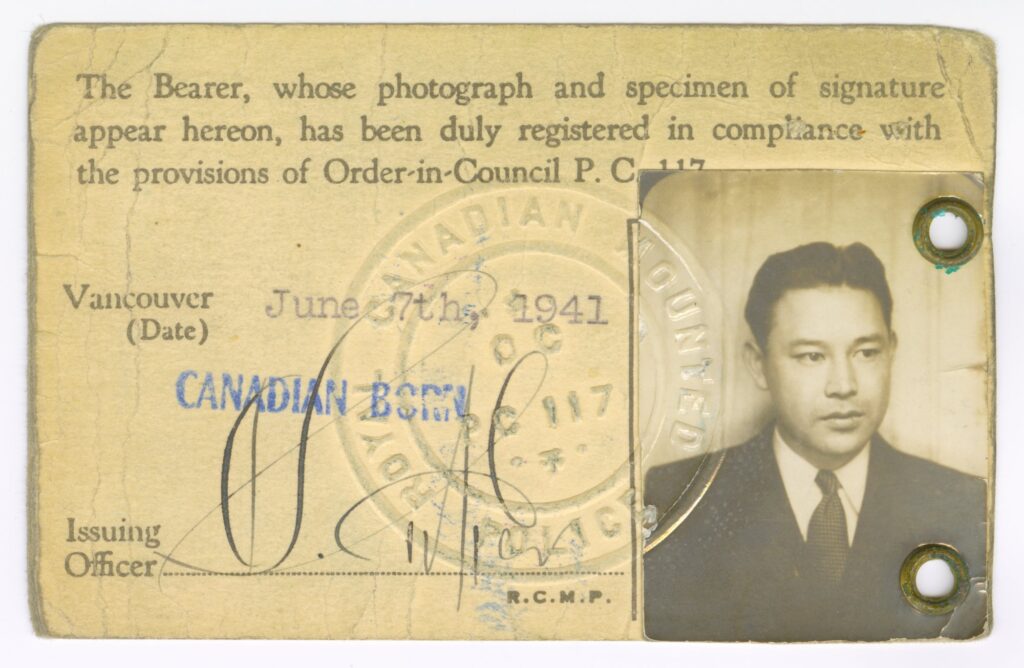

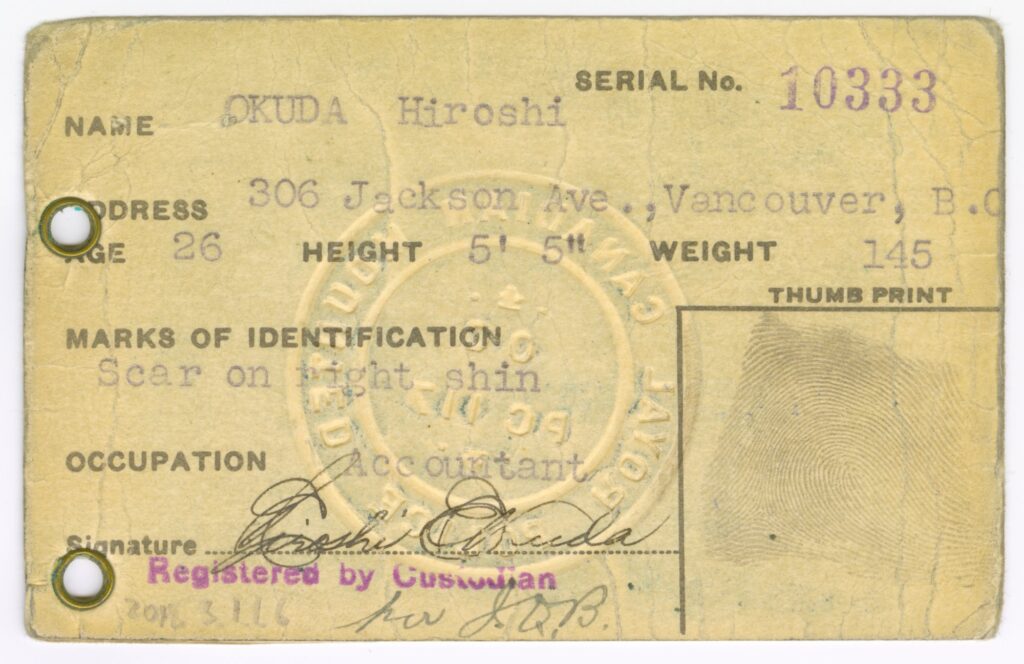

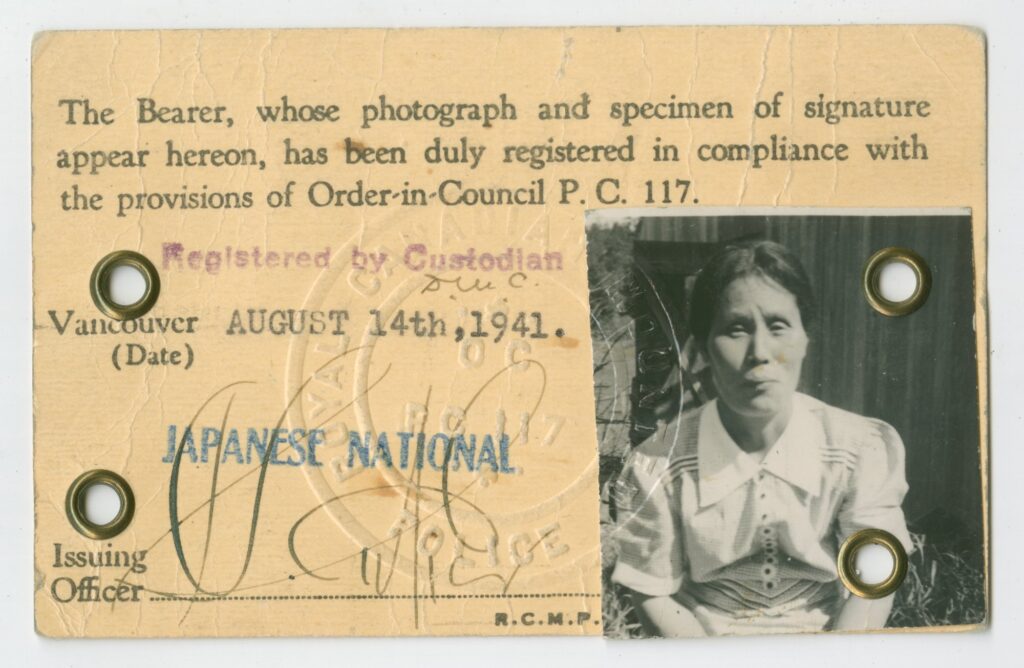

Beginning on March 4, 1941, all people of Japanese origin aged 16 and older were ordered to register with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Registration, basically marking all Japanese Canadians as enemy aliens, was based on a federally appointed advisory group’s recommendation (Robinson, 2017). Pink cards were assigned to naturalized Canadians, white to Canadian-born, and yellow to Japanese nationals (Theurer and Oue, 2021, p. 122-123). Prime Minister Mackenzie King told members of his Liberal party in the House of Commons that the Japanese were being as helpful as possible in the registration process. A. W. Neill, Member of Parliament for Comox-Alberni, snapped, “Whatever the opinion of the Prime Minister or of the government here, we in British Columbia are firmly convinced that once a Jap, always a Jap.” (Adachi, 1976, p. 195).

A secret letter was written by RCMP Commissioner S. T. Wood, dated 1942 August 5 to William S. Stephenson (subject of the book “A Man Called Intrepid”). Stephenson was the head of British Security Coordination, based in New York City, New York during the Second World War.

The letter said “We have had no evidence of espionage or sabotage among the Japanese in British Columbia. The situation has changed considerably since the report was written, and most of these people are now in isolated areas outside the protected area, and those at present in Vancouver will be removed by the first of November next. These consist largely of women and children…The fact remains, however, that we have searched without let-up for evidence detrimental to the interests of the state and we feel that our coverage has been good, but to date no such evidence has been uncovered”.

This letter was accompanied by a report prepared for William Stephenson, “Report on Japanese Activities in British Columbia”, written by Sgt. J. K. Barnes, Intelligence Section of British Columbia, “E” Division, RCMP, dated August 1942 (Barnes, 1942). Sgt. Barnes had been conducting surveillance on the Japanese Canadian community for several years before issuing the report. The report and cover letter are archived in RCMP file RG18-F-3 Volume/box number 3569 at Library and Archives Canada.