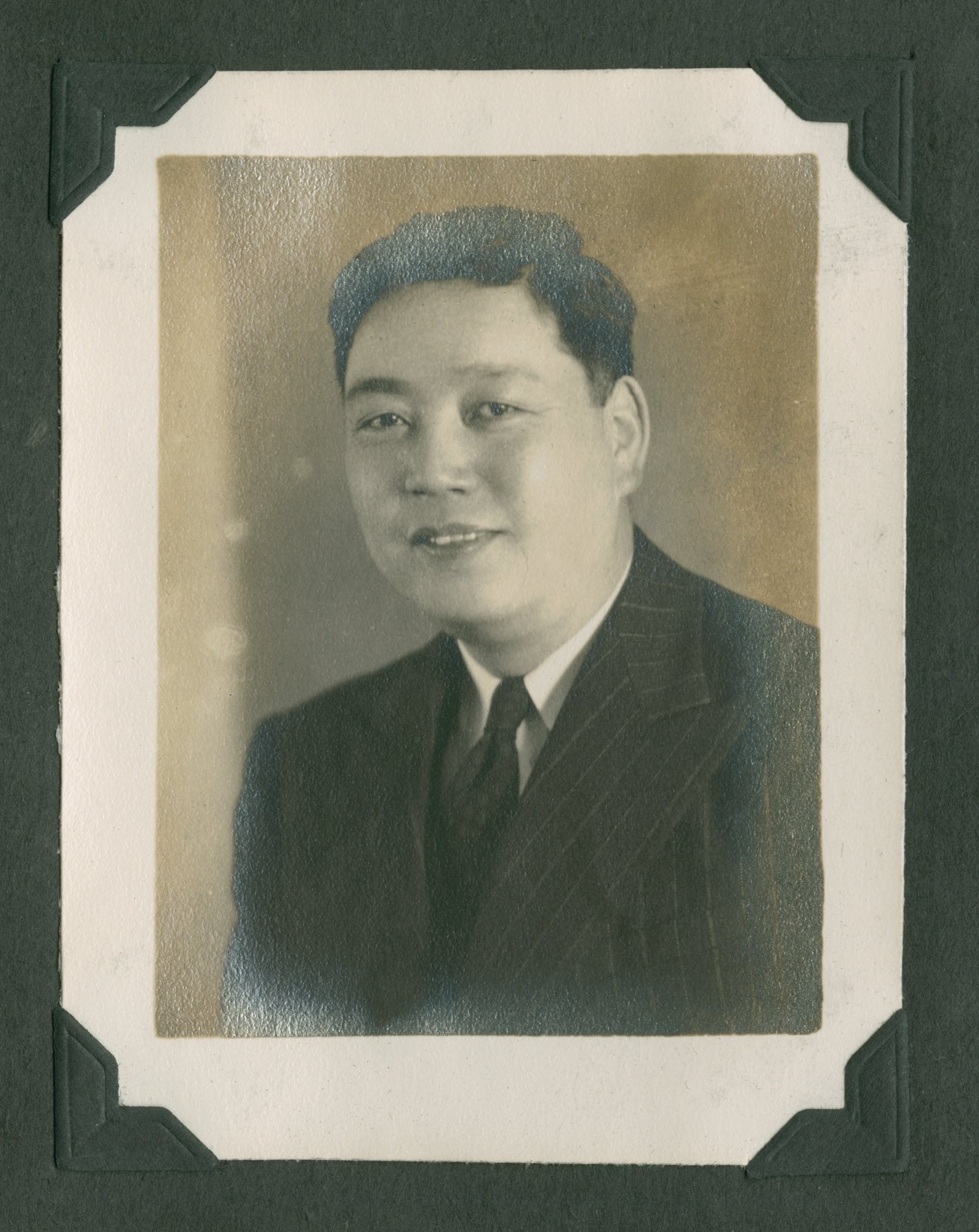

When the nisei returned home after their war service, they still faced the same government restrictions as before. The War Measures Act was still in place, and their government still considered them “enemy aliens.”

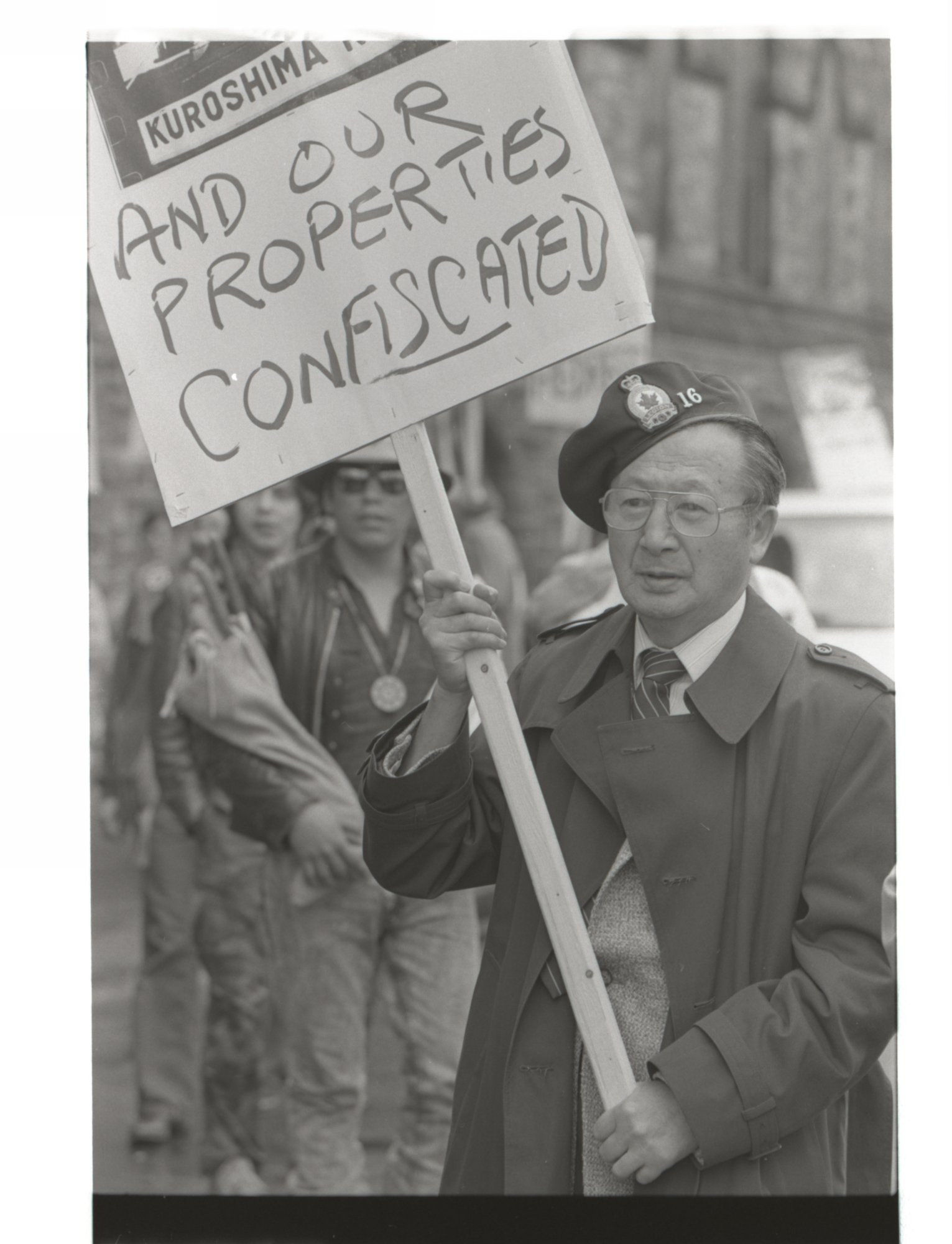

The parents of the nisei were now exhausted, unemployed, and impoverished after having their land and assets seized and sold without their permission at very low prices, and having to pay their own living expenses in internment camps. Bill Sasaki’s boat had been confiscated and sold. Buck Suzuki’s house had been confiscated and sold during the internment; he eventually purchased it again. Harold Hirose attempted to get his land near the Patullo Bridge back, but ironically it was sold under the Veterans Land Act, which was supposed to help returning veterans such as Hirose.

Restrictions remained on travel, business, residence, land ownership, and employment. Japanese Canadians were still required to carry their registration cards that had been issued in 1941. Nisei soldiers’ original 1941 registration cards had been handed over to the army when they enlisted, and were replaced with military ID cards. Most nisei veterans, insulted by this requirement, did not re-register (Ito, p. 279). A year after the war ended, veteran Frank Moritsugu returned home to St. Thomas, Ontario. He had an angry encounter with an RCMP officer who asked him to replace the photo on his registration card (at his own expense) because it was worn out; he reported this incident to the New Canadian newspaper.

Roy Ito reported a similar incident that happened to Tom Matsuoka, who had served from 1941 to 1946 in Europe and was badly injured in Germany:

“Tom Matsuoka of Alberta, a five-year army veteran, became angry with an RCMP officer who badgered him to get a Japanese registration card. He wrote to the Minister of Veteran Affairs – ironically, it was Ian Mackenzie. ‘Give me and thousands of Japanese Canadians our freedom. I am treated like a criminal. My fingerprints, photograph and number are on a card I must always carry. I can’t go anywhere unless I am granted a travelling permit. I’m watched like a convict (Ito, p. 278)’.”