“On December 7, 1941, an event took place that had nothing to do with me or my family and yet which had devastating consequences for all of us – Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in a surprise attack. With that event began one of the shoddiest chapters in the tortuous history of democracy in North America. More than twenty thousand people, mostly Canadians by birth, were uprooted, their tenuous foothold on the West Coast destroyed, and their lives shattered to an extent still far from fully assessed. Their only crime was the possession of a common genetic heritage with the enemy (Suzuki, 1987, p. 11).

“The nisei hadn’t anticipated the treachery of the devastating ‘sneak attack” on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. That attack confirmed every bigot’s belief in the inherent deceit and untrustworthiness of the Japanese race (Suzuki, 1987, p. 56).

At the time of the Pearl Harbor attacks, three-quarters of Japanese Canadians were either naturalized or native-born Canadians (Izumi, 2024).

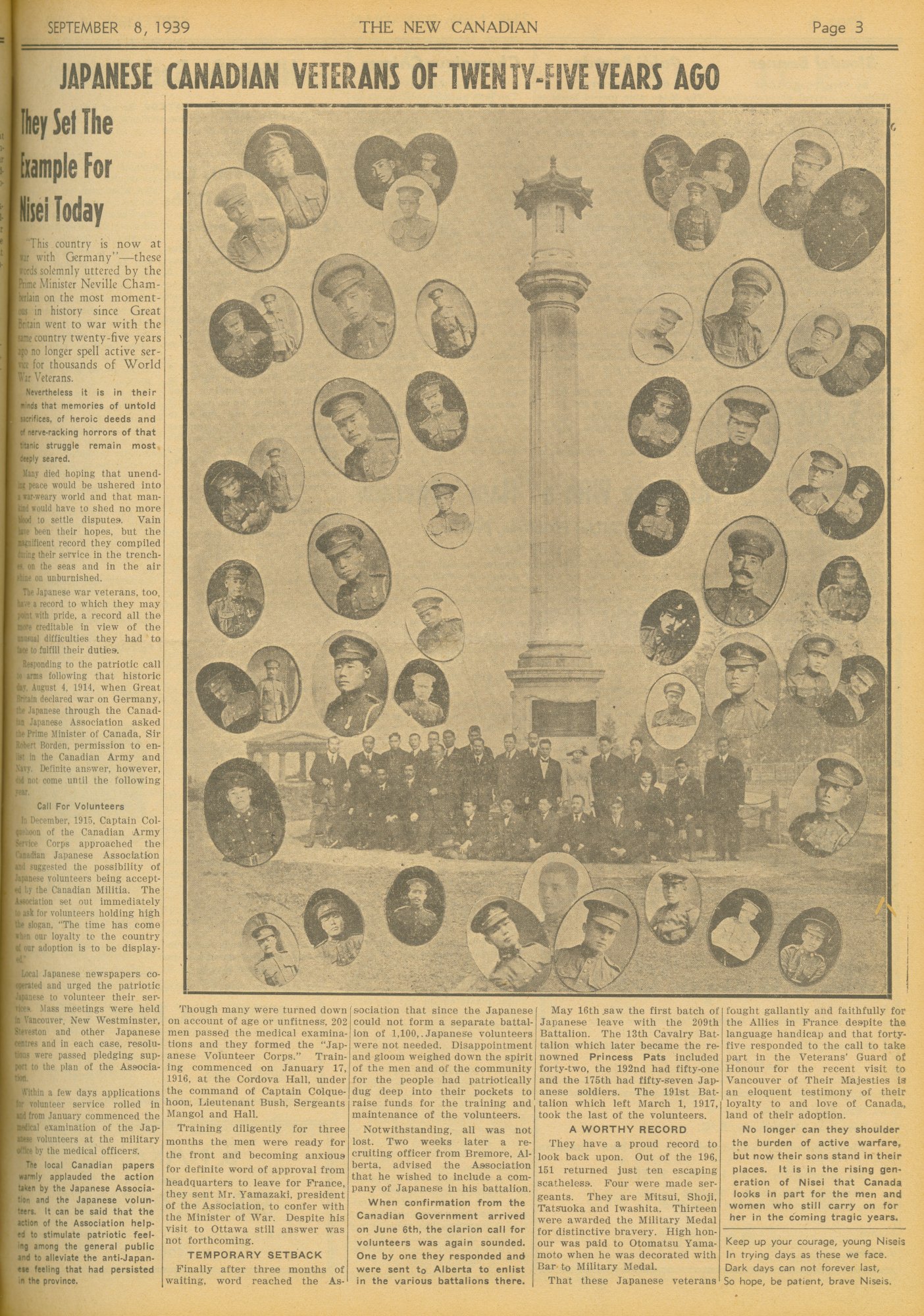

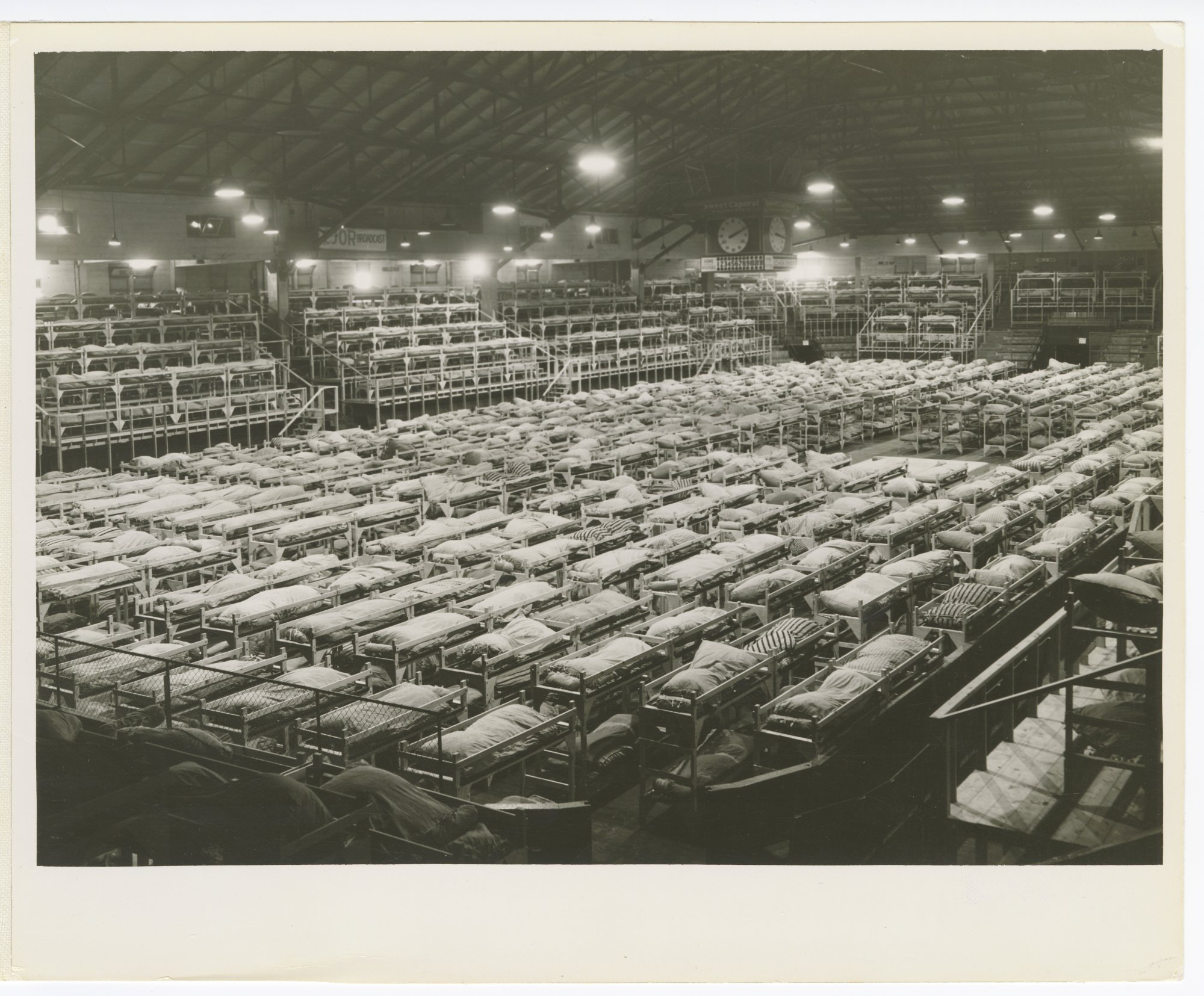

There were immediate repercussions on the JC community. All three Japanese language newspapers were shut down. Japanese language schools were closed. 39 respected leaders within the Japanese Canadian community were dragged on December 7 from their homes to the Vancouver Immigration building, then moved to P.O.W. camps in Seebe, Alberta, and Petawawa, Ontario, eventually being incarcerated in July 1942 in the Angler P.O.W. camp in Ontario (Okazaki, 1996). The 39 included a Buddhist minister, manager of a logging company, Japanese language teachers and Japanese language newspaper editors. They were considered “fifth columnists” by the RCMP because they were powerful and influential. 1200 Japanese fishing boats were confiscated; boats were towed to a dispersal centre and many boats were damaged. Licenses of Canadian citizens of Japanese descent were suspended. There were mass firings of hotel, railway, mill, and factory workers throughout the west coast. Homes and businesses owned by Japanese families were vandalized. On December 16, the lantern on the Japanese Canadian War Memorial in Stanley Park was extinguished. The lantern was finally relit 44 years later, on August 2, 1985 by First World War veteran Sergeant Masumi Mitsui (Wakayama, 2005). Everyone of Japanese descent aged 16 years and older, regardless of citizenship, was ordered to register with the Registrar of Enemy aliens.

“The newspapers were full of reports of Japanese espionage and sabotage on the west coast. ‘Japs go home’ signs appeared. The Chinese people started wearing ‘I’m Chinese’ buttons to make sure they were not mistaken for Japanese and assaulted. The declaration of war against Japan caused panic and enabled irrational fear and racism to influence decisions and actions at every level, from local school boards to the federal government in Ottawa (Theurer and Oue, 2021, p. 128)”.

In January of 1942, nisei at the University of British Columbia who were enrolled in the Canadian Officer Training Corps were ordered to turn in their uniforms. The 72 Japanese Canadian students at UBC, mainly nisei, were urged to leave (Ito, 1984, p. 138). They were unable to complete their university studies or missed their graduation ceremonies when they were sent away from Vancouver later in 1942.