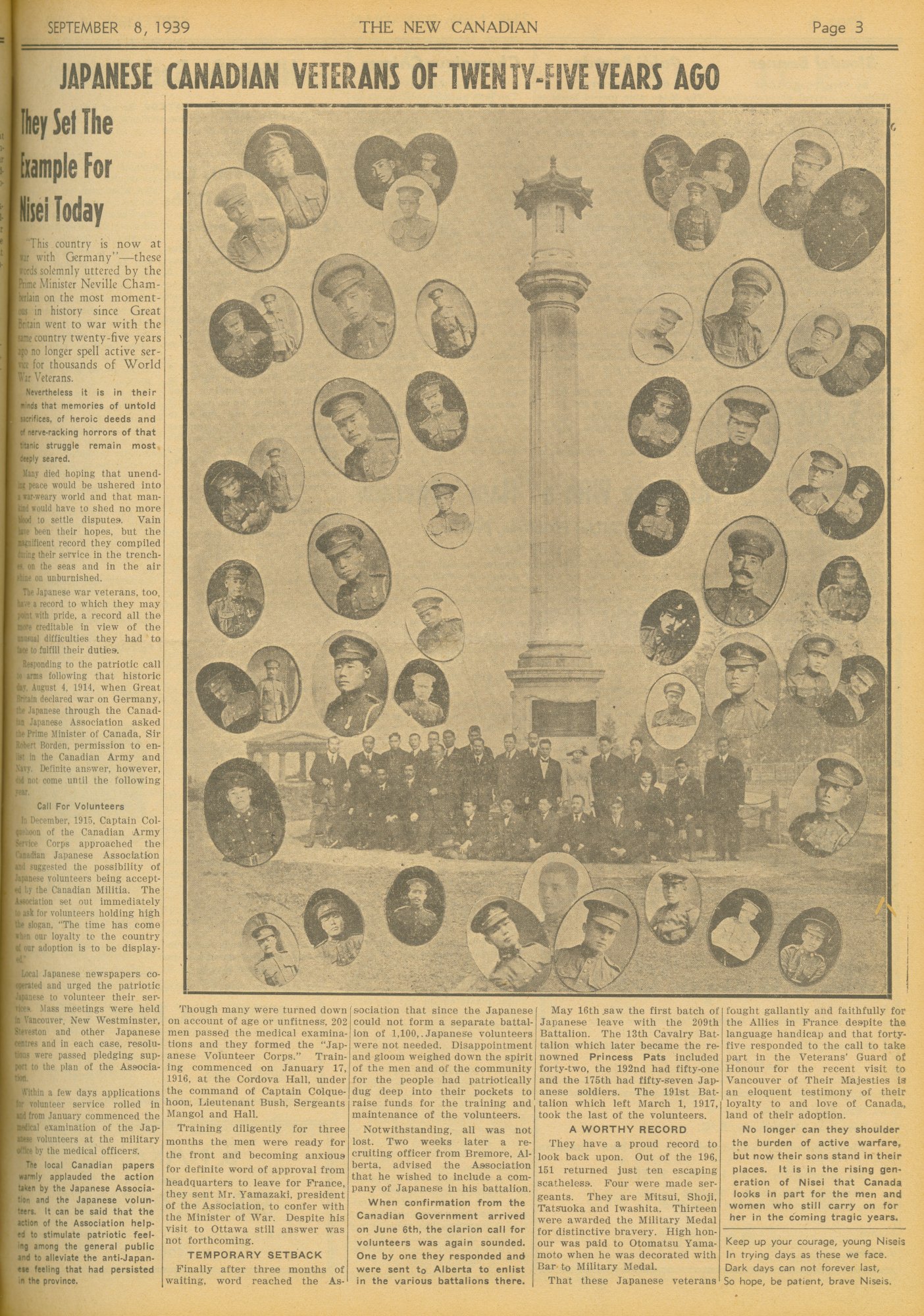

Opposition to enlistment of Japanese Canadians in the Canadian military came from many directions: the Canadian public, the government, and from the families of internees.

From 1942 until 1945, Japanese Canadians were banned from participating in the Canadian Forces, although many tried very hard to enlist and were turned down. Despite the ban, 32 nisei served in the Canadian military at this time, as nisei outside of BC had been able to enlist before Pearl Harbor. Many of this group experienced combat in Europe.

At a conference in Ottawa on January 8 and 9, 1942, the issue of nisei serving in the armed forces was raised. The 32-member Pacific Joint Services Committee, representing the army, navy and air force recommended nisei enlistment, but the five committee members from BC were strongly opposed and suggested instead that able-bodied male adult Japanese nationals be removed from the province (Theurer and Oue, 2021, p. 133). On January 10, Ian Mackenzie, the chairman, sent a private letter to Prime Minister King stating his opinion that nisei should not be permitted to enlist (Ito, 1984, p.141).

There had been a tentative plan proposed at the same conference to organize a Civilian Corps of Japanese, which would allow nisei to participate in the war effort. An Order-in-Council was passed by the Cabinet in February 1942, but due to anti-Japanese public opinion, the plan was dropped (Ito, 1984, p. 144-145).

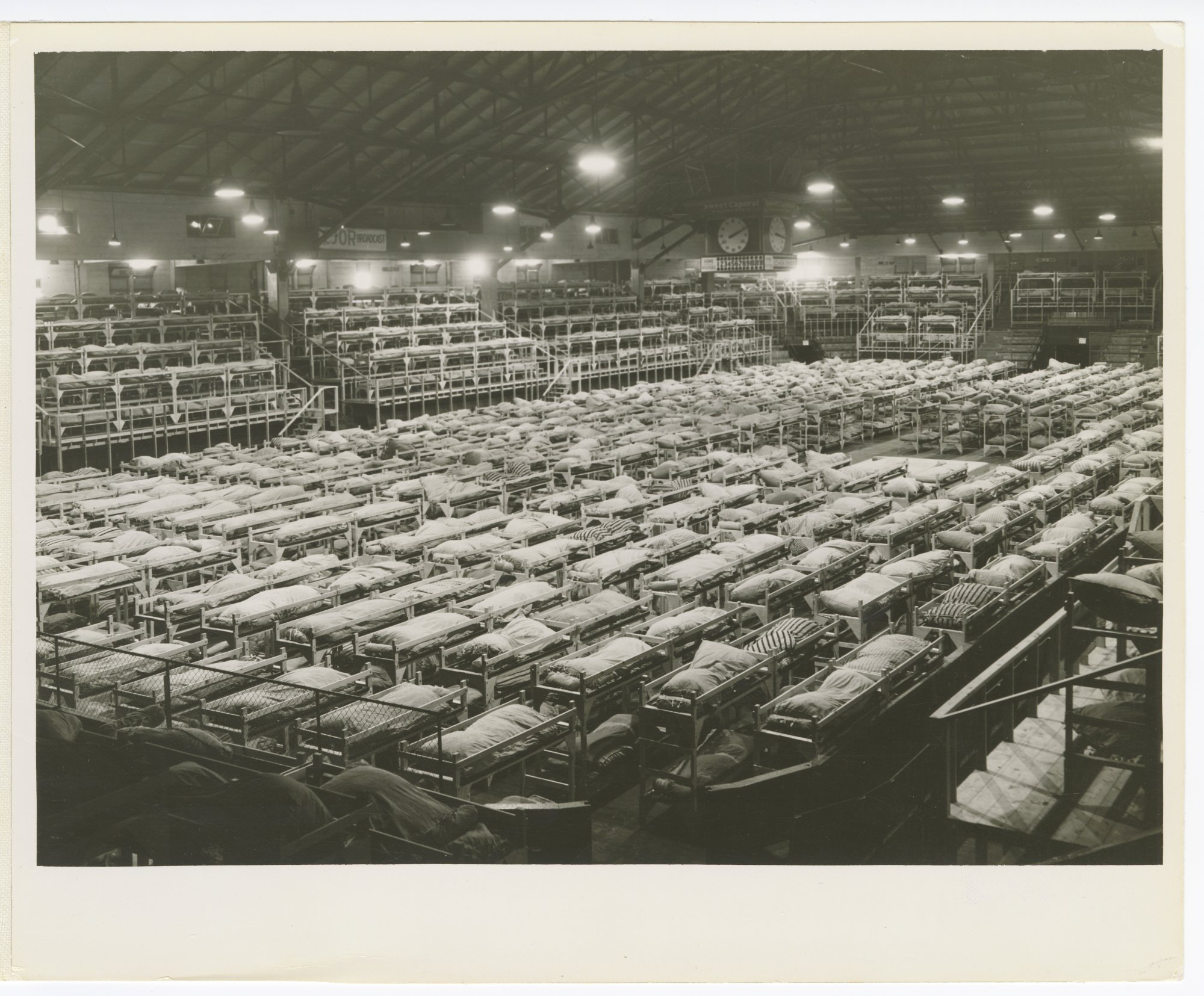

Soon after, Order-in-Council P.C. 1486 was introduced, and the removal of all “enemy aliens” began from the Protected Zone in BC.

The Japanese Canadian Committee for Democracy promoted the service of nisei in the Canadian army in order to demonstrate their loyalty, stating that nisei were willing to fight against Japan if necessary (Ito, 1984, p. 195). In January 1945, a raucous public meeting was held in Toronto in order to discuss this issue. The chairman, Eiji Yatabe, discussed the well-known success of the Japanese American 100 Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team as an example of why nisei should demonstrate their loyalty to their country (Obata, 2000; Ito, 1984, p. 195).

“I can recall violent threats, false accusations, and angry shouting matches in every direction. It was chaos. Finally, it came to a vote. Should the JCCD seek the elimination of the government policy barring Japanese Canadians from the Armed Forces? Those present at the meeting overwhelmingly rejected our proposal. I couldn’t believe the response. Then in a moment of spontaneity, the entire executive stood up and resigned en masse right then and there and almost all the male members of our JCCD executive volunteered to serve overseas once the restrictions against us were lifted (Obata, 2000)”.

The executive members who resigned, then enlisted soon after, included Roger Obata, George Tanaka, and Eiji Yatabe. Kinzie Tanaka (who was born in Japan) was later accepted for enlistment but did not serve due to the end of the war (Ito, 1984, p. 305).

“The conflict within our community arose from the fact that some people felt very bitter towards the Canadian government because of the expulsion, incarceration, and relocation ordeal, and wanted nothing to do with helping out a country that had treated its own citizens so shamefully (Obata, 2000)”.

Some nisei who enlisted were disowned by their families, who were very bitter over the internment (Broadfoot, 1977, p. 305).

“First, they won’t let us join up when we’re in BC. Then they kick us out of the place like we’re no good and spies and they put us in camps all over the country, and then when the British say they want us, they raise a fuss and say ‘No, these men are Canadian citizens. They go to war like Canadians’. Funny business (Broadfoot, 1977, p. 307)”.

In 1944, the BC Security Commission office in Toronto was collecting names and Identity numbers of nisei who were willing to enlist in the army for General Service, but did not publicize this fact. Lists dated November 13, 1944 and December 13, 1944 include the names of nisei located in Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec.

The irony that nisei were volunteering to serve the country that was persecuting them was expressed in an editorial by Allan P. Allsebrook of Kaslo in the October 28, 1944 issue of the New Canadian newspaper. The editorial was written in response to an anti-Japanese letter posted in the Nelson Daily News.

“Is he aware that the majority of our able-bodied young nisei — homeless, driven, bewildered, shamelessly robbed of their possessions, reviled, spat upon, and humiliated…are ready and willing to vindicate their honour and loyalty to Canada by enlisting for service? But our priceless politicians will have none of them (Allsebrook, 1944).”