July 5, 1950 marked the first battle between North Korean and American forces in the war, at Osan, south of Seoul. The 24th Infantry Division’s Task Force Smith was a battalion combat team hastily deployed from Japan to delay the advance of a North Korean division before the arrival of reinforcement US troops in Korea. The Americans were outnumbered and not well-equipped. They were able to delay the North Koreans for only a brief time before they retreated with heavy casualties (Kikoy, 2018).

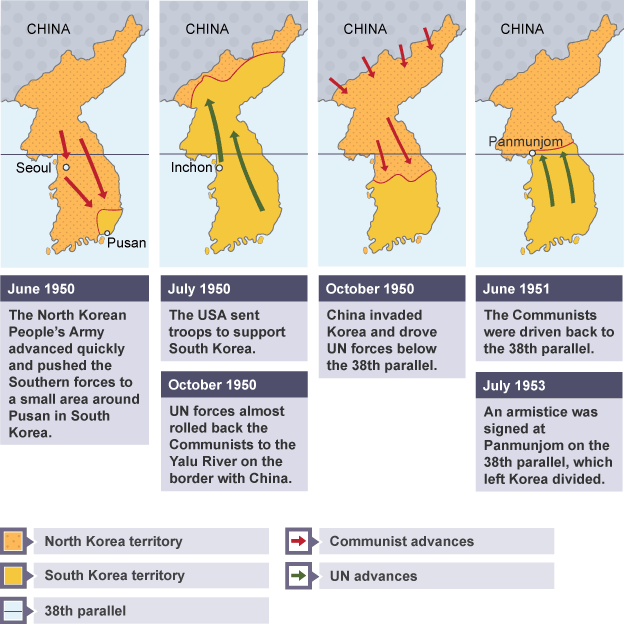

In the summer of 1950, the North Korean army continued pushing south…”crushing all opposition, until it left the defenders clinging to a tiny toehold in a perimeter surrounding the port of Pusan (Busan) at Korea’s southern tip. The ROK troops had simply melted away, leaving the Americans with a ragtag force scraped together in haste to defend the indefensible (Berton, 2001, p. 539).

The defense of the so-called Pusan Perimeter took place in August and September of 1950. The US Eighth Army had deployed from Japan in July 1950, and assumed command over the United Nations Forces (US, South Korean, and other nations’ ground combat units) fighting the North Korean invasion (The History Guy, 2017). UN Forces were commanded by General Douglas MacArthur. Soldiers found both the terrain and the weather to be very challenging. The landscape included rugged, step mountains, and deep valleys. The weather ranged from extremes of hot and humid in the summer to bitterly cold in the winter. By September 12, the North Korean troops had reached their southernmost point of advance. The UN Forces were able to hold off any further North Korean advance, and thus prevented the takeover of South Korea by North Korean forces. The North Korean army by this time had been reduced in size and strength, and it was lacking supplies, including armor; these facts were unknown to the UN forces.

General MacArthur proposed a risky amphibious assault on Incheon, the lightly defended port of Seoul on the west coast of South Korea. It would enable the UN to bypass Pusan, seize Incheon, free Seoul from its North Korean occupiers, and force the occupiers back behind the 38th Parallel (Berton, 2001, p. 540). This proposal received initial opposition from MacArthur’s superiors, but it was finally approved on August 28. The landing at Incheon, named Operation Chromite, began on September 15, 1950. It caught the North Korean Army by surprise and was a success. As MacArthur had predicted, the North Koreans fled north to the 38th Parallel, relieving the South Korean forces in the Pusan Perimeter (Berton, 2001, p. 541). Seoul was liberated on September 25.

MacArthur erroneously believed, at this stage, that the Korean War would be over in approximately one month. In reality, the Incheon landing, rather than ending the war, re-started it. He requested and was given permission on September 29 to cross the 38th Parallel into North Korea and destroy the retreating North Korean army, which had crossed the 38th Parallel on the previous day (Berton, 2001, p. 543). This was a shift from the original policy, which had been to defend South Korea.

On October 18, UN Forces captured the capital of North Korea, Pyongyang. North Korean forces, by now heavily decimated, retreated towards the Chinese border, pursued by UN Forces. MacArthur was warned by advisors, including Canadians, that these actions could provoke the intervention of Chinese forces in the war (Berton, 2001, p. 543). Chinese premier Chou En-lai warned the UN that China would not allow Americans to cross the 38th Parallel (Berton, 2001, p. 544).

As UN Forces approached the Yalu River bordering China on November 25, 130,000 Chinese soldiers were waiting for them. The Chinese soldiers, heavily camouflaged, had crossed the river by night into North Korea. They inflicted serious casualties on the lead units of the UN advance. The main body of UN forces retreated into South Korea, marking a significant and humiliating defeat for the UN forces (The History Guy, 2017).

UN forces, mainly US Marines, fought with Chinese forces at the Chosin Reservoir in a 17-day battle in freezing temperatures. 30,000 UN troops were surrounded and attacked by 120,000 Chinese troops. Heavy casualties were inflicted on both sides. The UN force withdrew to the North Korean port of Hungnam. They were evacuated to South Korea, with many North Korean refugees. At this point, the UN had completely withdrawn from North Korea (Granfield, 2004, pg. 4; Millett, 2025).

On December 23, General Walton Walker, commander of the Eighth United States Army, was killed in a vehicle accident. He was replaced by Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgeway (Berton, 2001, p. 548).

Early in 1951, Seoul was recaptured by Chinese and North Korean forces, and UN troops were pushed back across the 38th Parallel (Granfield, 2004, pg. 121).

At the end of January 1951, the Eighth Army began a counter-offensive, inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy. On March 14, UN forces again captured Seoul, which had been badly damaged by the war, its population decimated (Berton, 2001, p. 554).

On April 11, 1951, U.S. President Truman relieved General Douglas MacArthur of his command because of insubordination and for publicly questioning the President’s war strategy. Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway replaced MacArthur as UN Commander (Granfield, 2004, p. 45).

The Chinese army launched the Spring Offensive in April of 1951 in order to force the United Nations Command off of the Korean peninsula. This was the last time that either side tried to inflict a crushing defeat on their opponent’s army. The two major battles of the Spring Offensive included the Battle of Kapyong and the Battle of Imjin River. In both cases, the UN forces were vastly outnumbered by their opponents. In the Battle of Kapyong, the 2nd Battalion of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry Regiment and the 3rd Battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment repelled a Chinese division of 5,000. The Canadians withstood multiple waves of attackers until the Chinese forces had been halted (Stairs and Foot, 2022). In the Battle of Imjin River, 4,000 members of the British 29th Brigade delayed 30,000 troops of the Chinese Army. 650 members of the Gloucestershire Regiment held their position for three days against more than 10,000 Chinese infantry. Most soldiers of the Gloucestershire Regiment were killed or captured, but their actions blunted the Chinese offensive and allowed UN forces to repel the Chinese forces moving towards Seoul (Berton, 2001, p. 561; Millett, 2025).